GUIDELINES

For the

Management of Moderate Acute

Malnutrition, in Ethiopia

Final version

September, 2012

ENCU/EWRD/MOARD

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Tel: 0115 52 35 56

e-mail: isaackm@dppc.gov.et

http://www.dppc.gov.et

Acknowledgments

The DRMFSS and Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH) would like to express its appreciation to the Emergency

Nutrition Coordination Unit (ENCU) for leading the process to develop these guidelines. We are also

grateful to the Humanitarian Response Fund (HRF) for providing the financial support required to produce

this document. These guidelines were developed by Ms. Emily Mates, an independent consultant engaged

by UNICEF with funding from the HRF.

We would like to express our appreciation to the very many people who contributed to these guidelines.

Many thanks are due to members of both the MAM Technical Working Group (TWG) and the Multi Agency

Nutrition Task Force (MANTF) in Ethiopia, who provided valuable input, comments and feedback to

improve the document.

Early Warning and Response Directorate (EWRD) of the Disaster Risk Management and Food Security

Sector, of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 2012.

ii

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................................................................... ii

Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................................... iii

List of Boxes, Figures and Tables ........................................................................................................................... iv

List of Annexes .......................................................................................................................................................... v

Glossary of Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................... v

Definition of Terms................................................................................................................................................... vii

Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 1

Current health and nutrition situation in Ethiopia ...................................................................................................... 1

Current MAM situation in Ethiopia ............................................................................................................................ 2

The aim of these guidelines...................................................................................................................................... 3

Chapter 1. Overview and classification of malnutrition.......................................................................................... 4

1.1 Types of malnutrition...................................................................................................................................... 4

1.2 Causes of malnutrition ................................................................................................................................... 5

1.3 Identification of acute malnutrition using WHO growth standards (2006)....................................................... 7

1.3.1 Identification of Weight for Height Measurement (WFH) ratio using the reference tables ............................. 8

1.3.2 Identification of malnutrition using MUAC...................................................................................................... 9

1.4 Information sources that can provide information on the need to establish MAM treatment emergency

interventions ............................................................................................................................................................. 9

Chapter 2. Supplementary Feeding Interventions................................................................................................. 10

2.1 Description of supplementary feeding.......................................................................................................... 10

2.1.1 Objectives of setting up an SFP .................................................................................................................. 10

2.2 Planning the intervention ............................................................................................................................. 11

2.2.1 Staff ............................................................................................................................................................. 11

2.2.2 Supplies, equipment and transport .............................................................................................................. 11

2.2.3 Storage and Warehousing........................................................................................................................... 12

2.3 Types of Supplementary Feeding Programmes (SFPs)............................................................................... 12

2.3.1 Blanket Supplementary Feeding Programme (BSFP) ................................................................................. 13

2.3.1.1 Objectives of the BSFP ............................................................................................................................... 13

2.3.1.2 General criteria for establishing emergency BSFPs...................................................................................... 13

2.3.1.3 Case load estimation and beneficiary identification for BSFPs...................................................................... 13

2.3.1.4 Admission and discharge criteria for BSFP ................................................................................................. 14

2.3.1.5 When to Close emergency BSFPs ................................................................................................................ 14

2.3.2 Targeted Supplementary Feeding Programme (TSFP) ............................................................................... 14

2.3.2.1 Objective of the TSFP................................................................................................................................. 14

2.3.2.2 When to establish TSFPs............................................................................................................................ 15

2.3.2.3 Determining the case load for a TSFP ......................................................................................................... 15

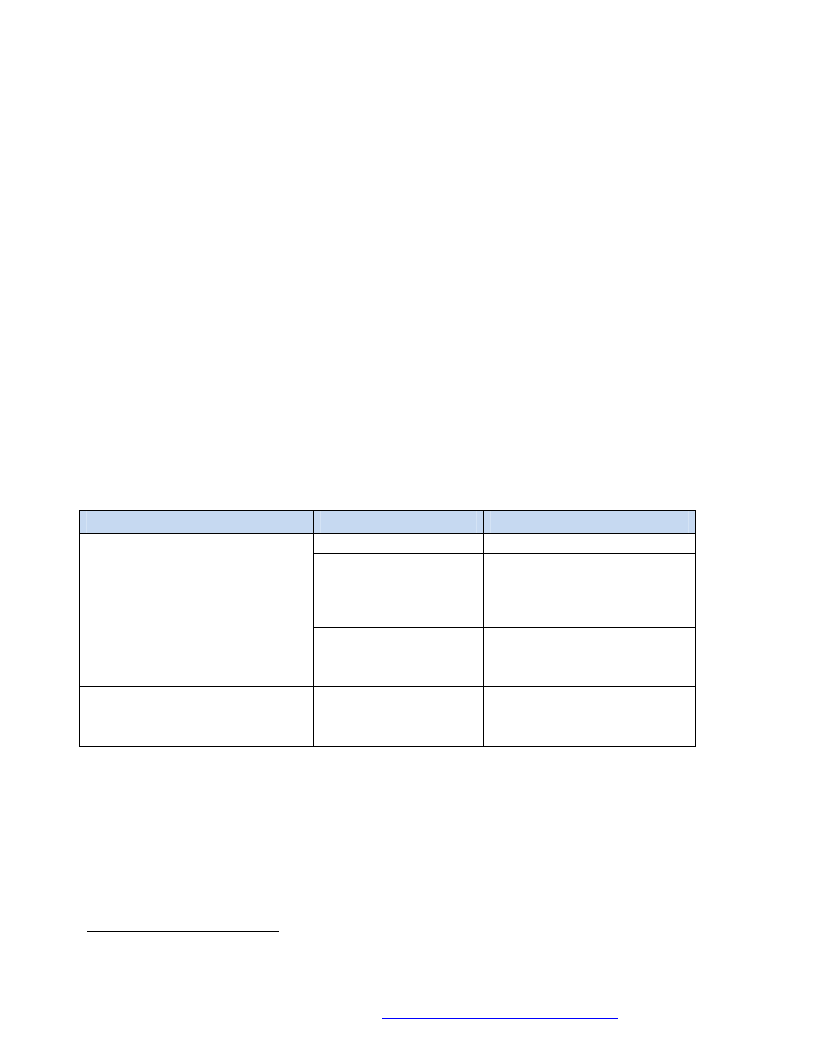

2.3.2.4 TSFP triage, diagnosis and beneficiary selection ......................................................................................... 16

2.3.2.5 Admission criteria for TSFP ....................................................................................................................... 18

2.3.2.5.1 MAM children 6-59 months.................................................................................................................... 18

2.3.2.5.2 MAM Pregnant and Lactating Women (PLW).......................................................................................... 19

2.3.2.5.3 MAM in other vulnerable groups (admission and discharge criteria)....................................................... 20

2.3.2.6 TSFP distribution procedures at the site for new and registered beneficiaries ............................................... 20

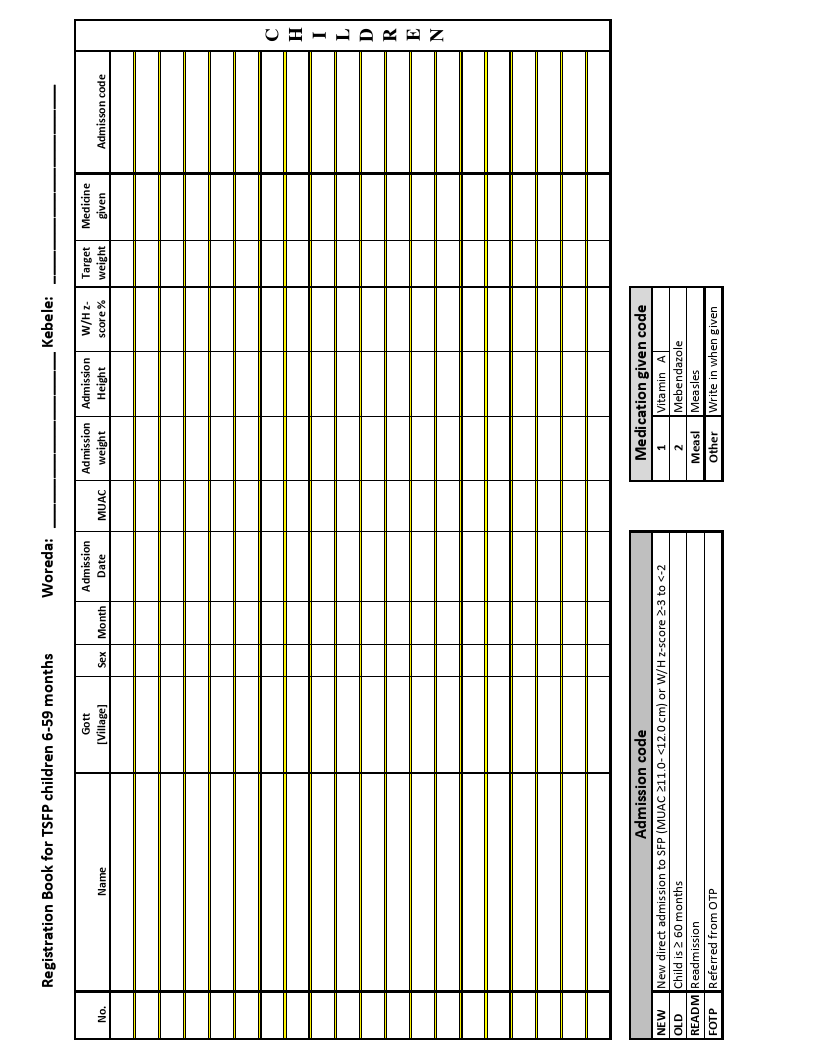

2.3.2.6.1 Beneficiary registration ................................................................................................................... 21

2.3.2.6.2 Routine treatment ........................................................................................................................... 21

2.3.2.6.3 Follow up procedures for those already registered in TSFP .............................................................. 21

2.3.2.6.4 Transfer to OTP or inpatient unit (TFU or SC) .................................................................................. 22

2.3.2.7 Nutrition counselling and education .......................................................................................................... 22

2.3.2.8 Supplementary food ration ........................................................................................................................ 22

2.3.2.8.1 Provision of the dry ration ............................................................................................................... 22

2.3.2.8.2 Premixing the ration........................................................................................................................ 23

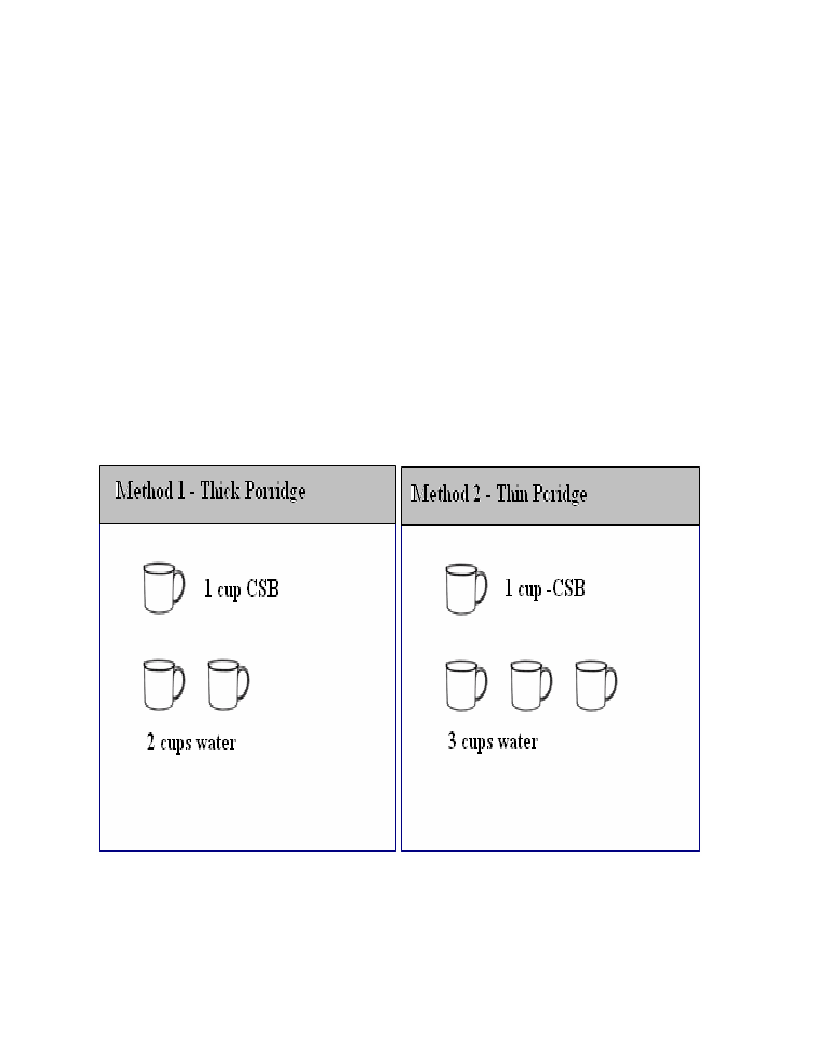

2.3.2.8.3 Cooking demonstrations.................................................................................................................. 23

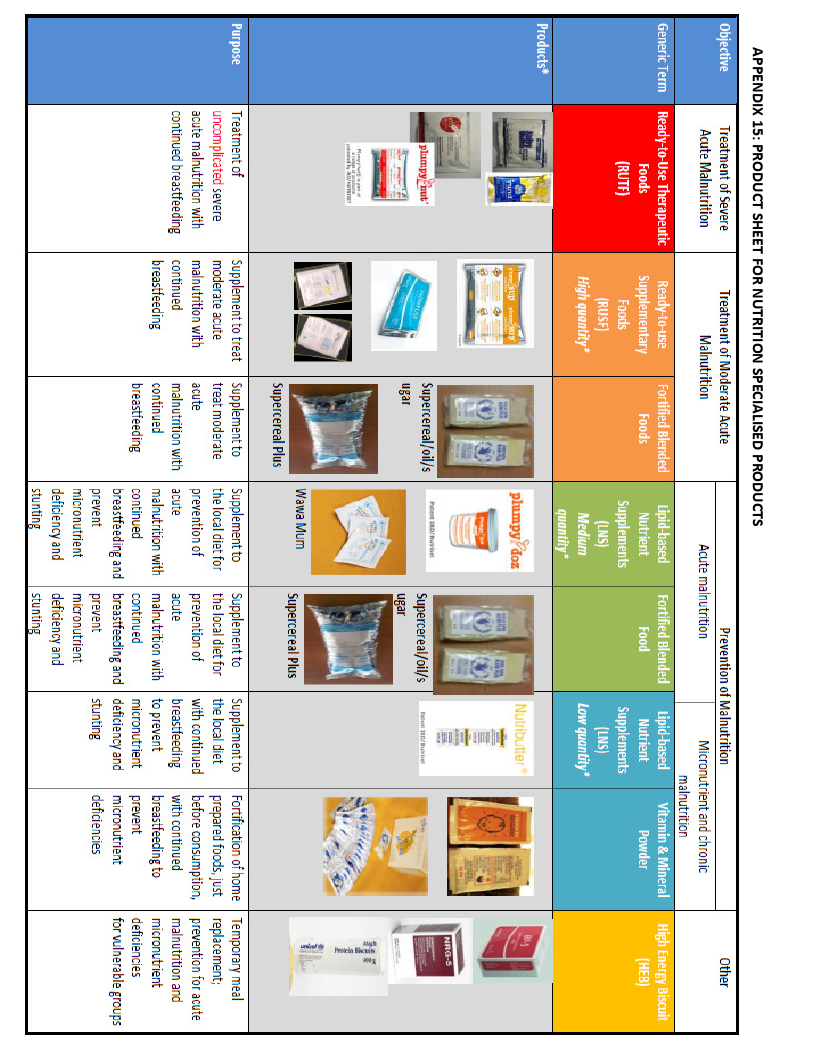

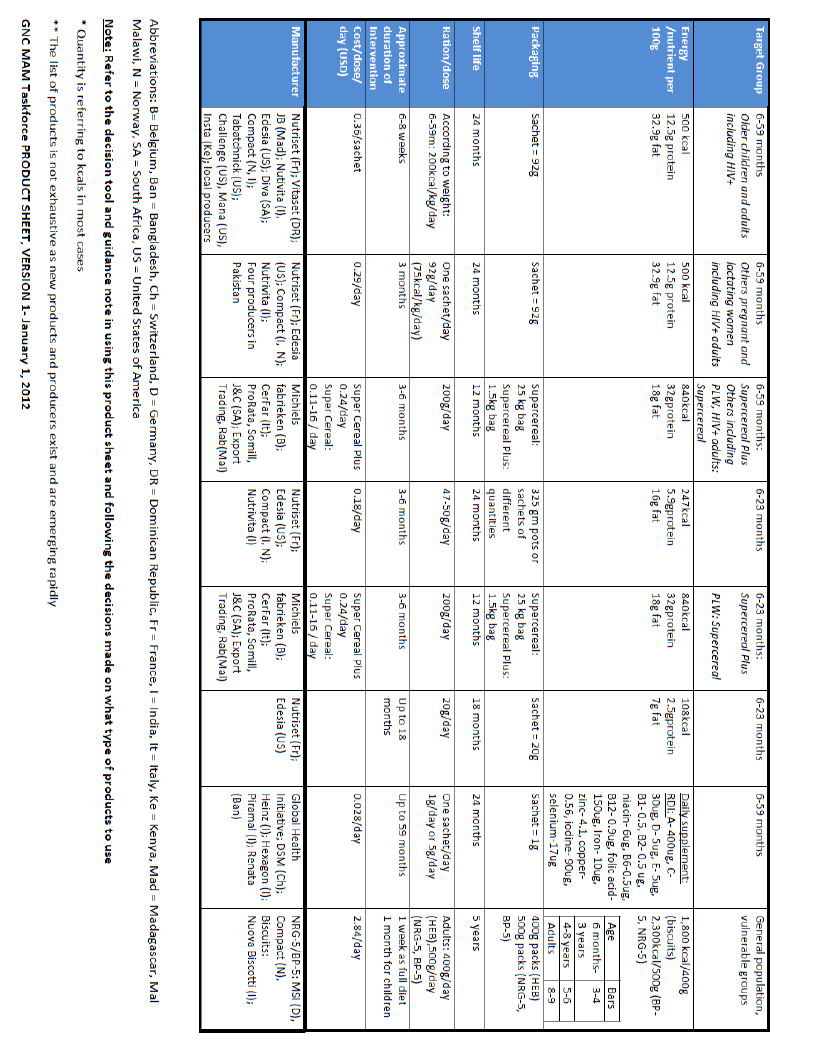

2.3.2.8.4 Newer products for the treatment of MAM ....................................................................................... 24

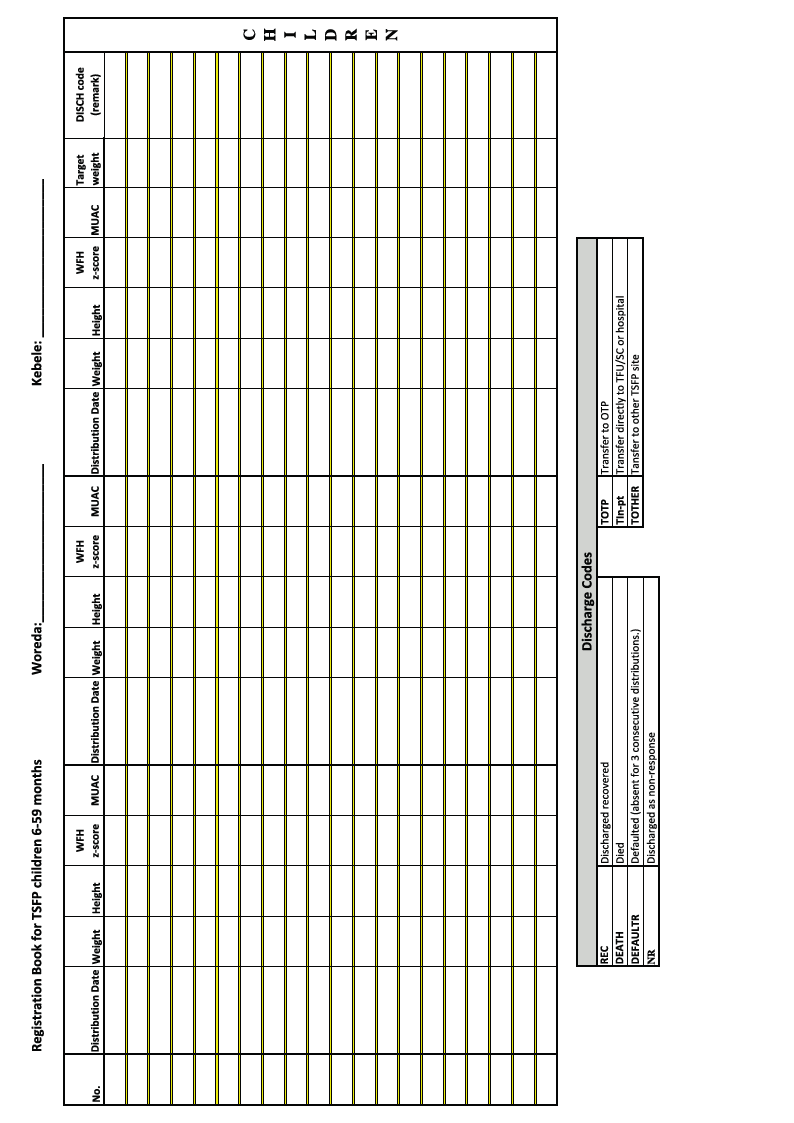

2.3.2.9 Discharge criteria ..................................................................................................................................... 24

2.3.2.9.1 Discharge recovered cured .............................................................................................................. 24

2.3.2.9.2 Discharges from TSFP other than recovered cured - children 6-59 months ....................................... 25

2.3.2.9.3 Discharges from TSFP other than recovered cured - PLW ................................................................. 26

2.3.2.10 When to close the emergency TSFP ........................................................................................................ 26

iii

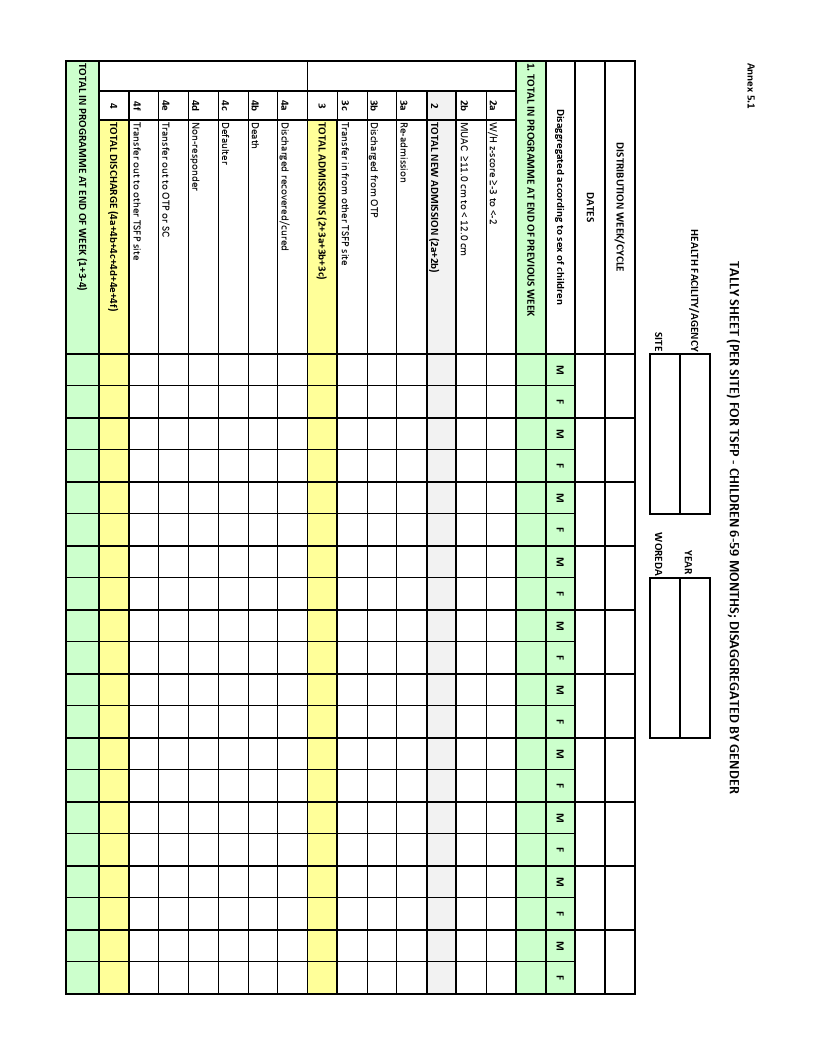

Chapter 3. Monitoring, reporting and coverage .................................................................................................... 27

3.1 Monitoring .................................................................................................................................................... 27

3.2 Reporting ..................................................................................................................................................... 28

3.2.1 Completing the monthly report .................................................................................................................... 28

3.2.2 Using the monthly reports to determine programme performance .............................................................. 28

3.3 Coverage ..................................................................................................................................................... 29

Chapter 4. Community mobilisation, nutrition counselling and education ....................................................... 32

4.1 Community mobilisation ............................................................................................................................... 32

4.1.1 Objectives of community mobilisation ......................................................................................................... 32

4.1.2 Information required prior to programming .................................................................................................. 33

4.1.3 Who should be involved in community mobilisation .................................................................................... 33

4.1.4 Supplies and training ................................................................................................................................... 33

4.1.5 Case finding and referral ............................................................................................................................. 34

4.1.6 Follow-up and home visits ........................................................................................................................... 34

4.2 Nutrition counselling and education ............................................................................................................. 35

4.2.1 Promotion of good hygiene at health facilities and distribution sites............................................................ 36

Chapter 5. Management of acute malnutrition in infants under-6 months (MAMI), maternal health, urban and

pastoralist issues ..................................................................................................................................................... 37

5.1 Management of acute malnutrition in infants < 6 months (MAMI) ................................................................ 37

5.1.1 Implications for Ethiopia from the MAMI project findings ............................................................................. 38

5.1.2 Identification and response.......................................................................................................................... 39

5.2 Maternal nutrition health .............................................................................................................................. 40

5.3 Urban and pastoralist issues........................................................................................................................ 41

5.3.1 Urban issues ............................................................................................................................................... 41

5.3.2 Pastoralist issues ........................................................................................................................................ 42

References................................................................................................................................................................ 43

List of Boxes, Figures and Tables

Box 1: The Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP)....................................................................................................... 2

Box 2: Technical review of the Management of Acute Malnutrition in Infants (MAMI) Project: Current evidence, policies,

practices & programme outcomes ...................................................................................................................................... 38

Box 3: Urban issues .......................................................................................................................................................... 41

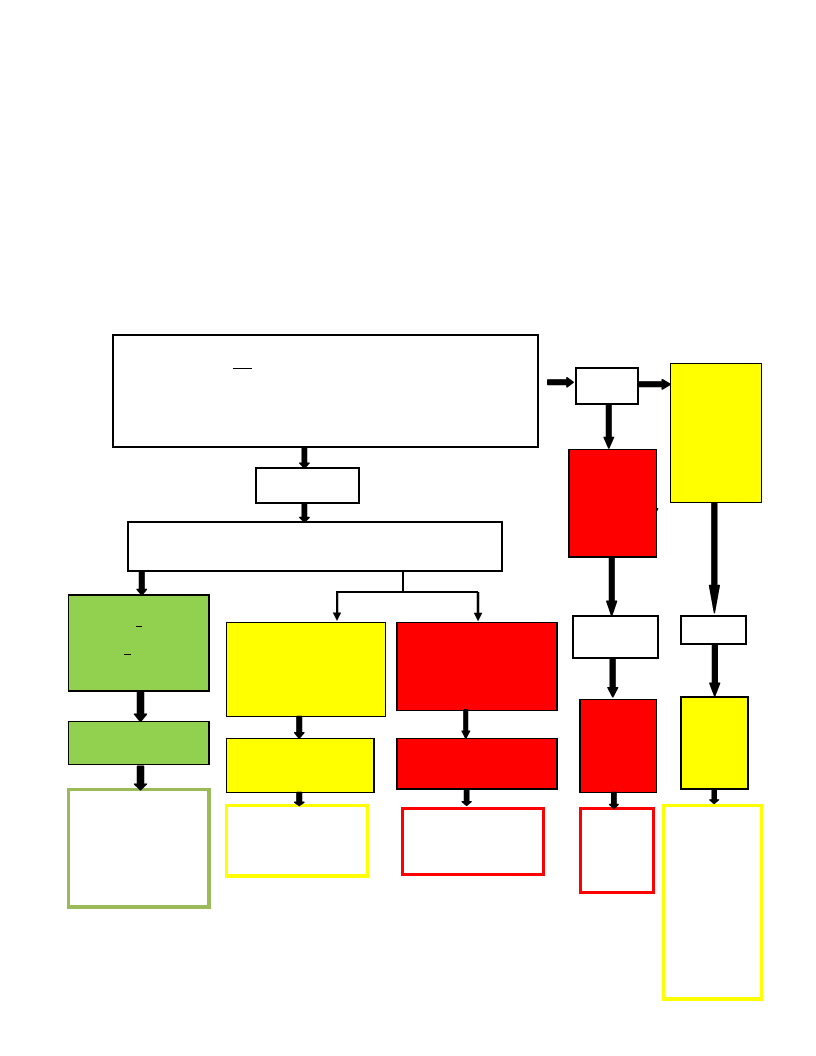

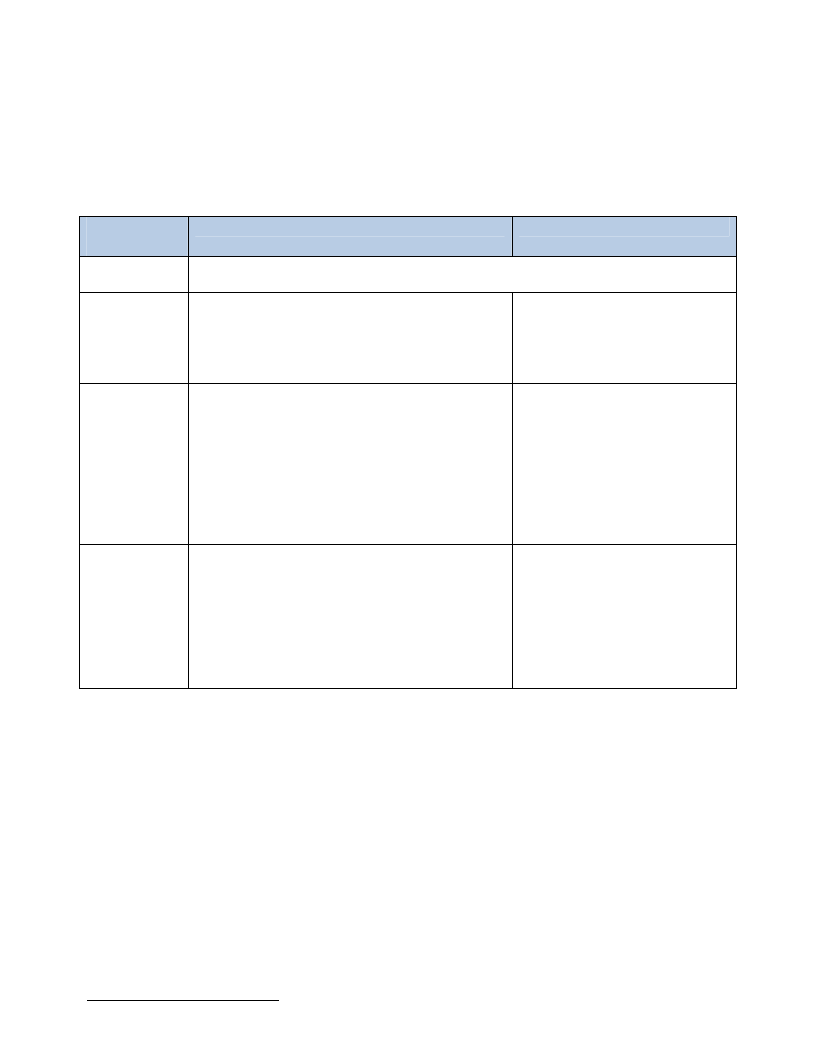

Figure 1: Types of Malnutrition............................................................................................................................................ 4

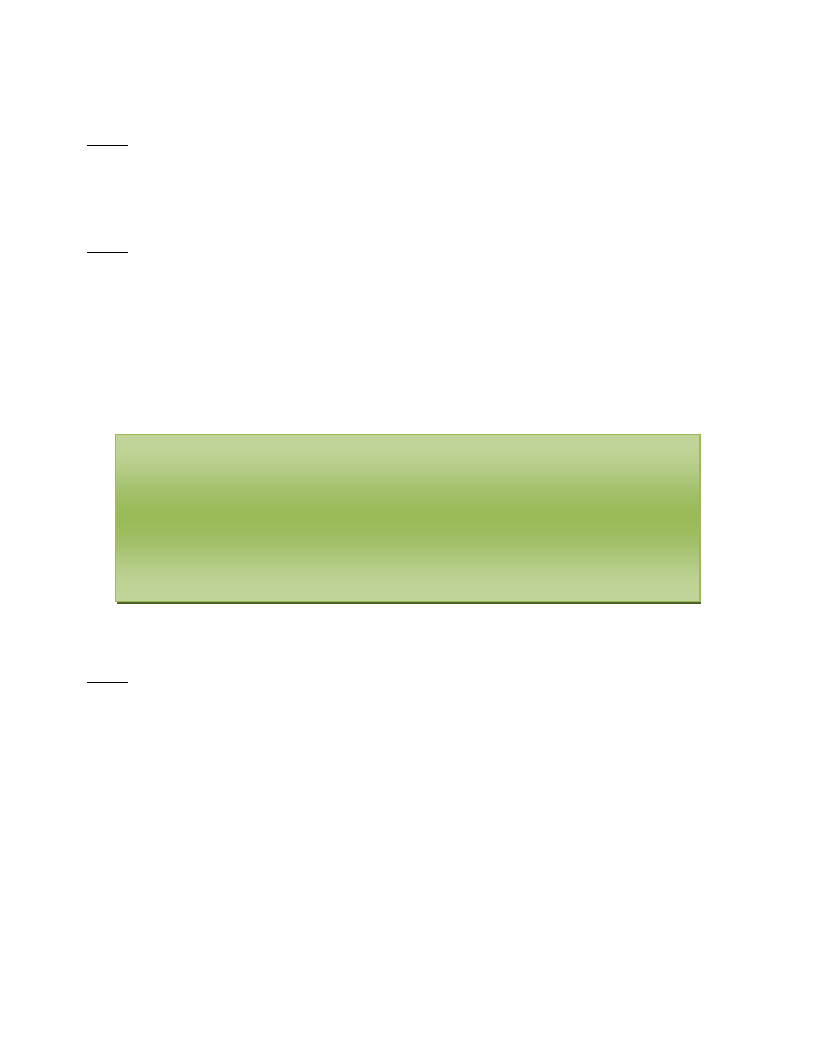

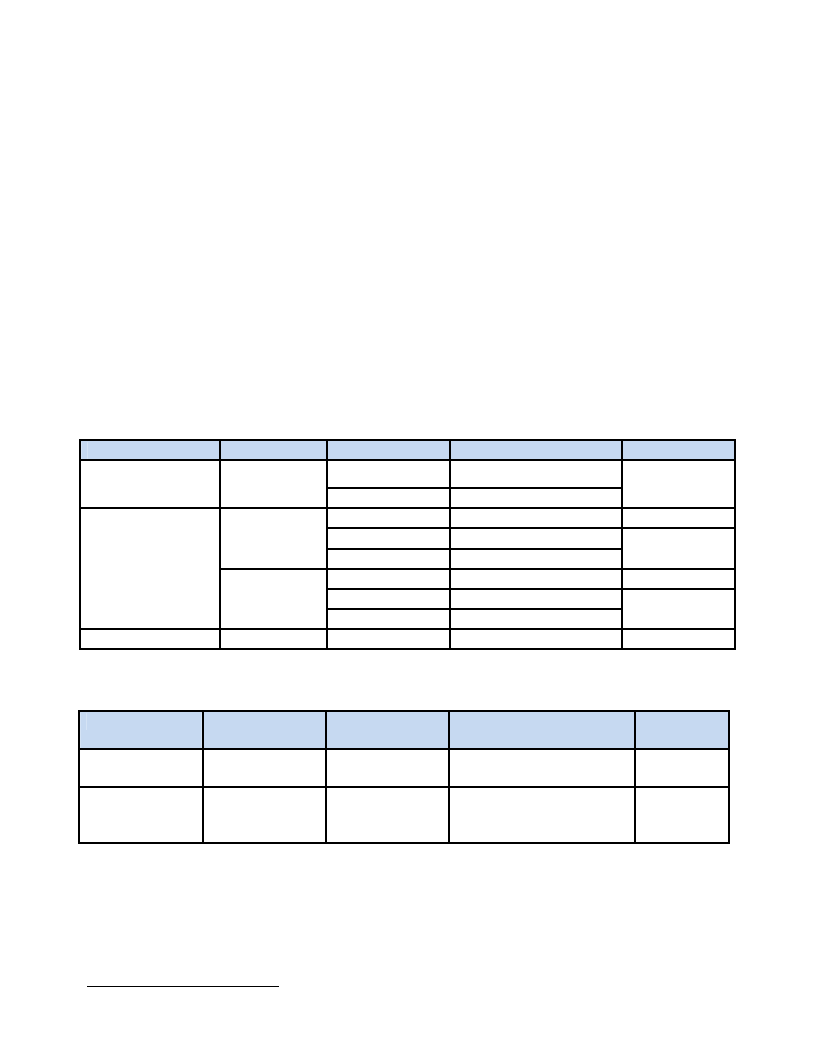

Figure 2: UNICEF conceptual framework for the determinants of nutritional status ............................................................ 6

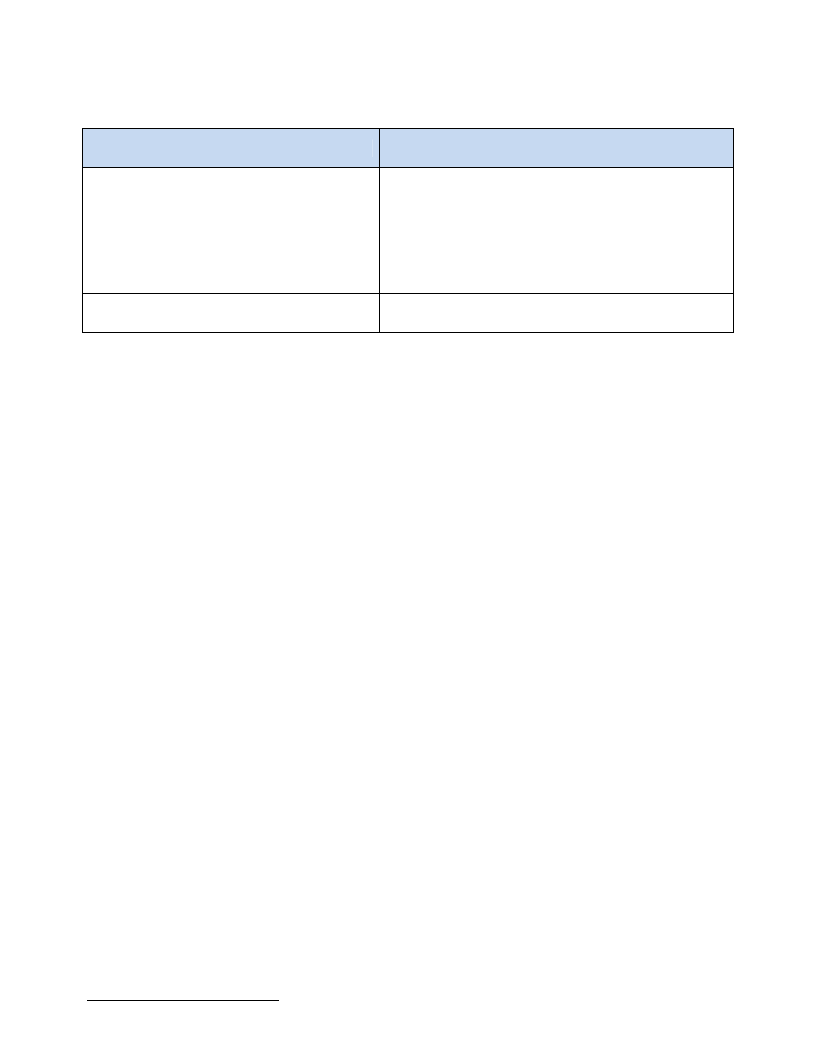

Figure 3: The important features of warehousing and storing food commodities .............................................................. 12

Figure 4: Triage process for children 6 – 59 months screened or referred to distribution site or health facility for

Management of Acute Malnutrition (for infants 0 - 6 months, refer to SAM guidelines) .................................................. 16

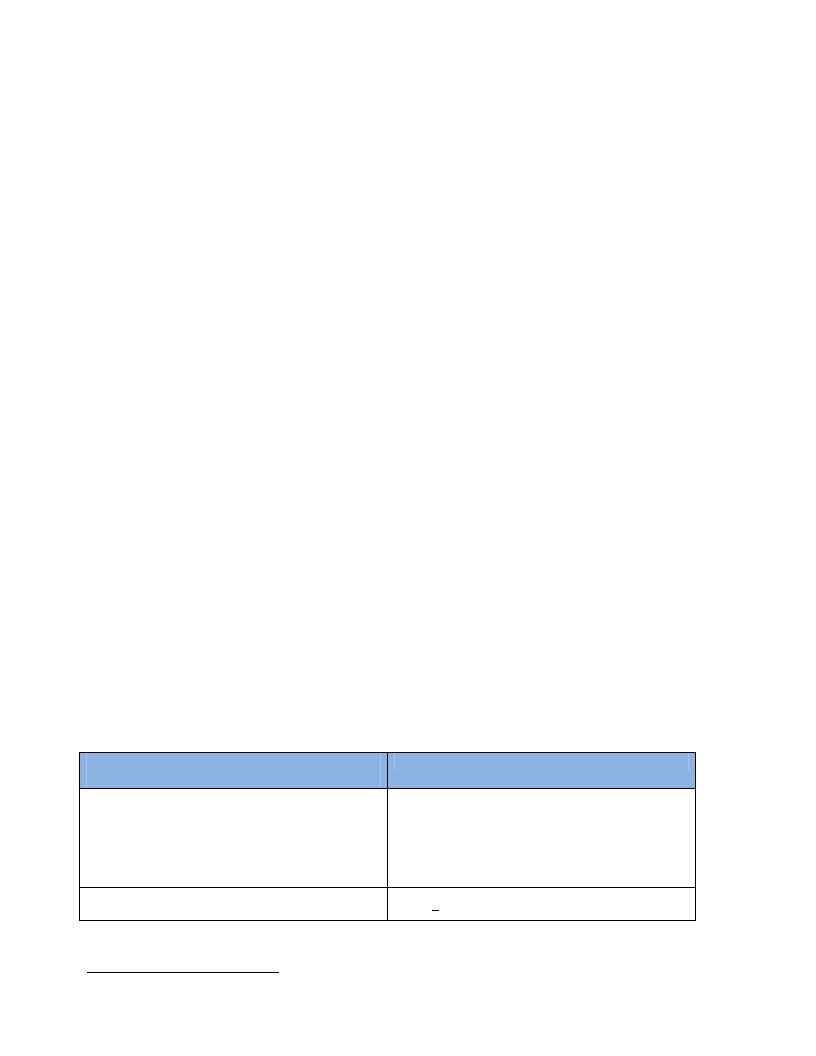

Figure 5: Formulas for calculating period and point coverage........................................................................................... 30

Table 1: Target group and type of measurement .............................................................................................................. 18

Table 2: Summary of Admission Criteria for TSFP............................................................................................................ 19

Table 3: Recommendations for admission and discharge criteria for other vulnerable groups suffering from MAM ......... 20

Table 4: Summary of routine medicines for children ......................................................................................................... 21

Table 5: Summary of routine medicines for pregnant and lactating women ...................................................................... 21

Table 6: Criteria for MAM beneficiaries, discharge ‘recovered/cured’ ............................................................................... 24

Table 7: Calculation of indicators for the monthly report (example given is for Under-5 children)..................................... 29

iv

List of Annexes

Annex 1

Annex 2

Annex 3

Annex 4

Annex 5

Annex 6

Annex 7

Annex 8

Annex 9

Annex 10

Annex 11

Annex 12

Annex 13

Annex 14

Annex 15

Annex 16

Annex 17

Annex 18

Annex 19

Annex 20

Annex 21

Annex 22

Annex 23

WFH Reference Table (WHO GS 2006)

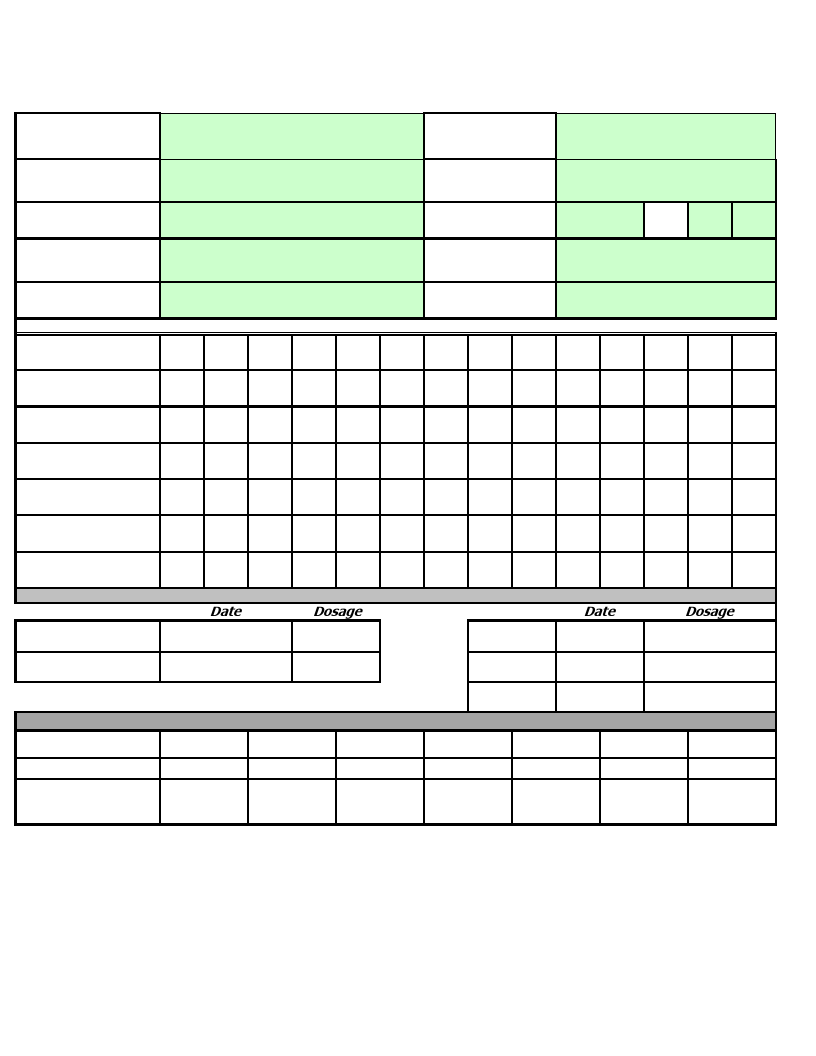

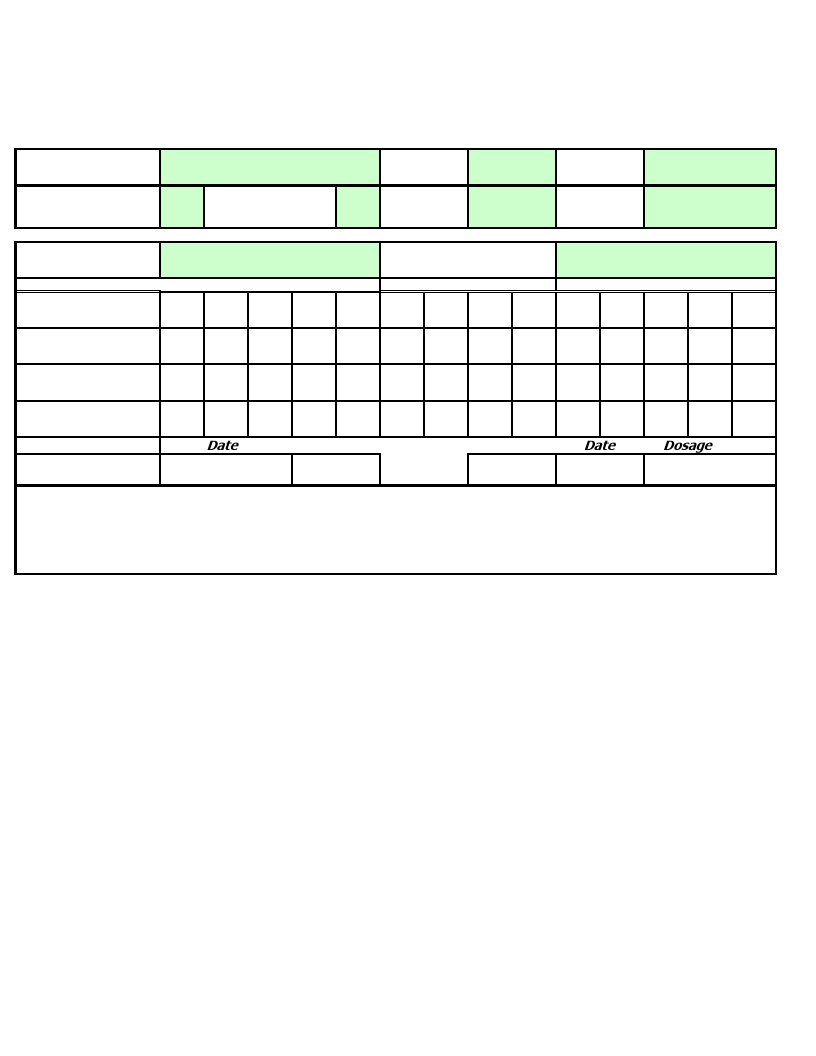

TSFP Ration Card: Children 6-59 months and PLW

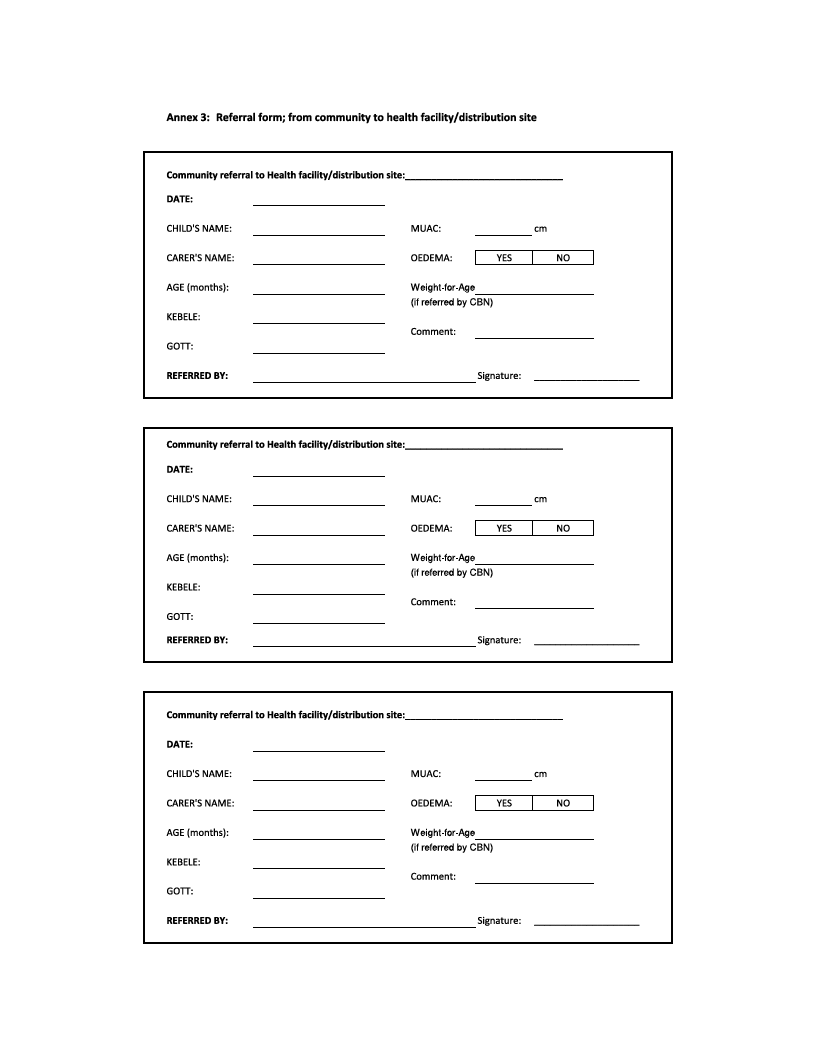

Referral Slip from Community to Distribution Site

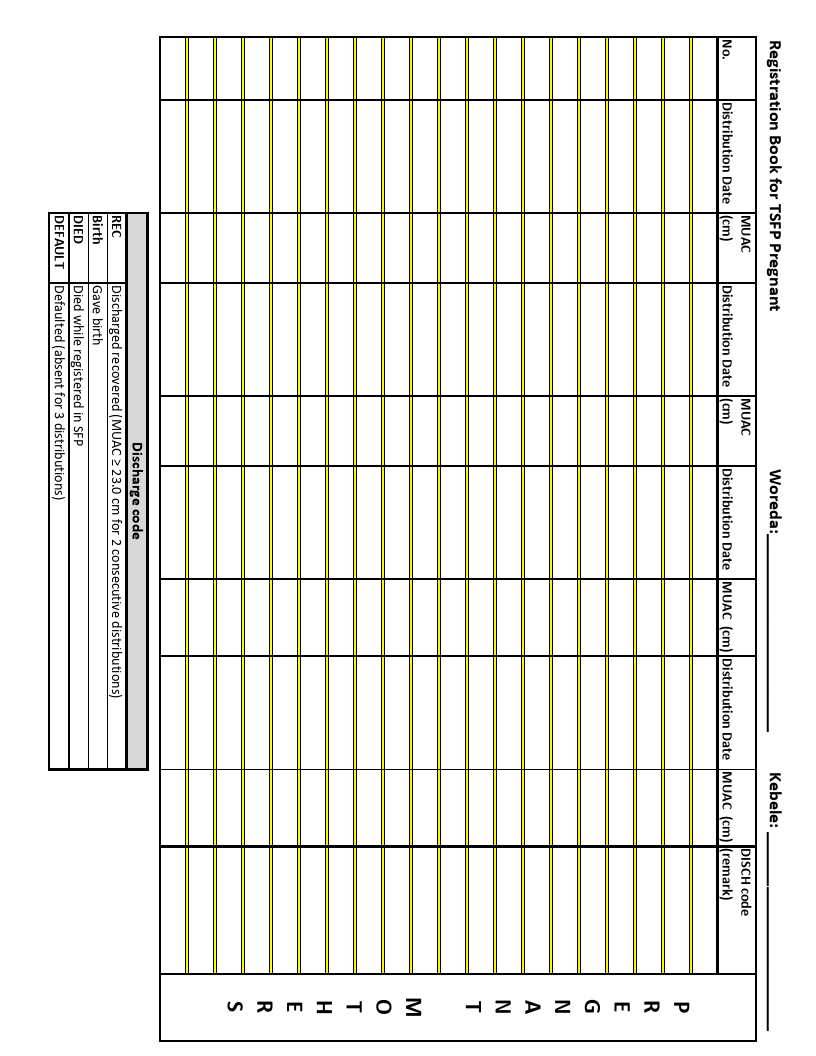

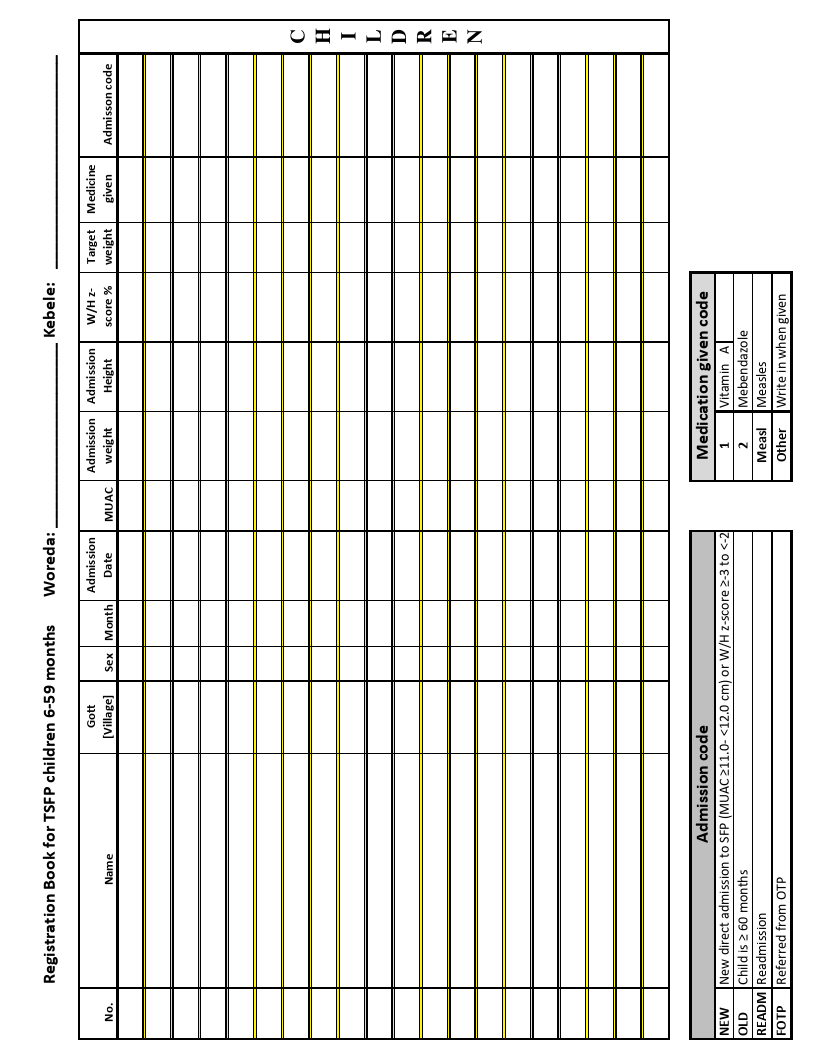

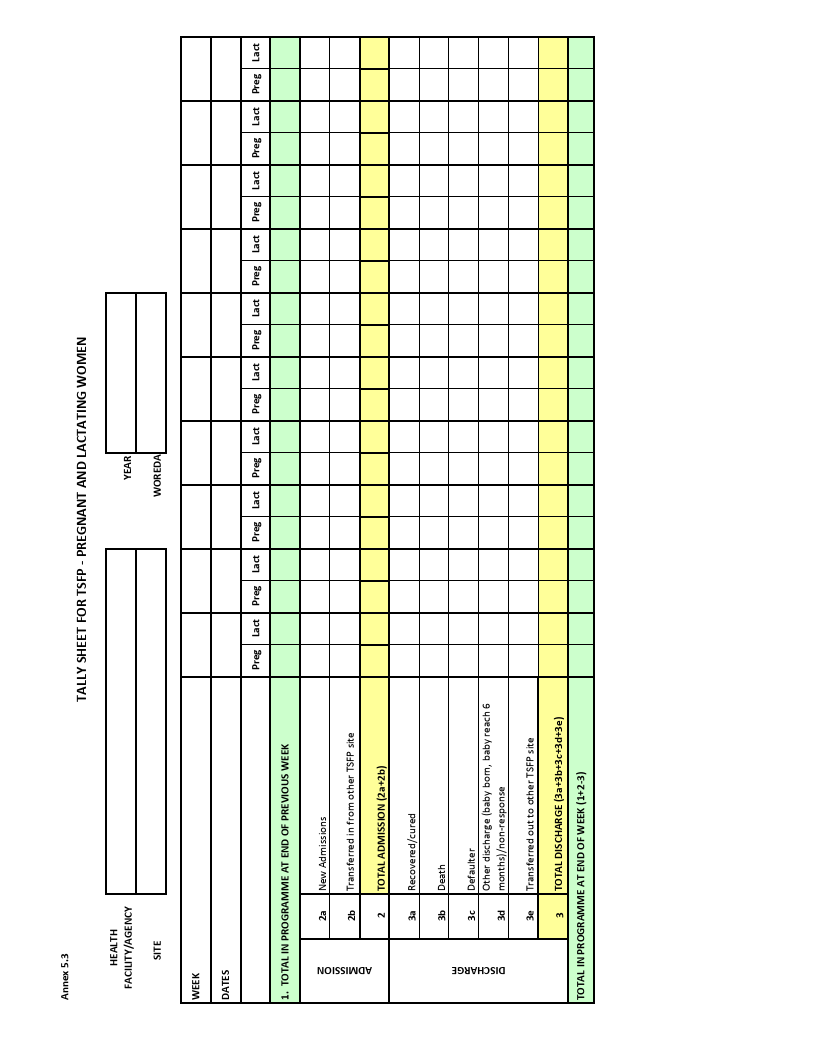

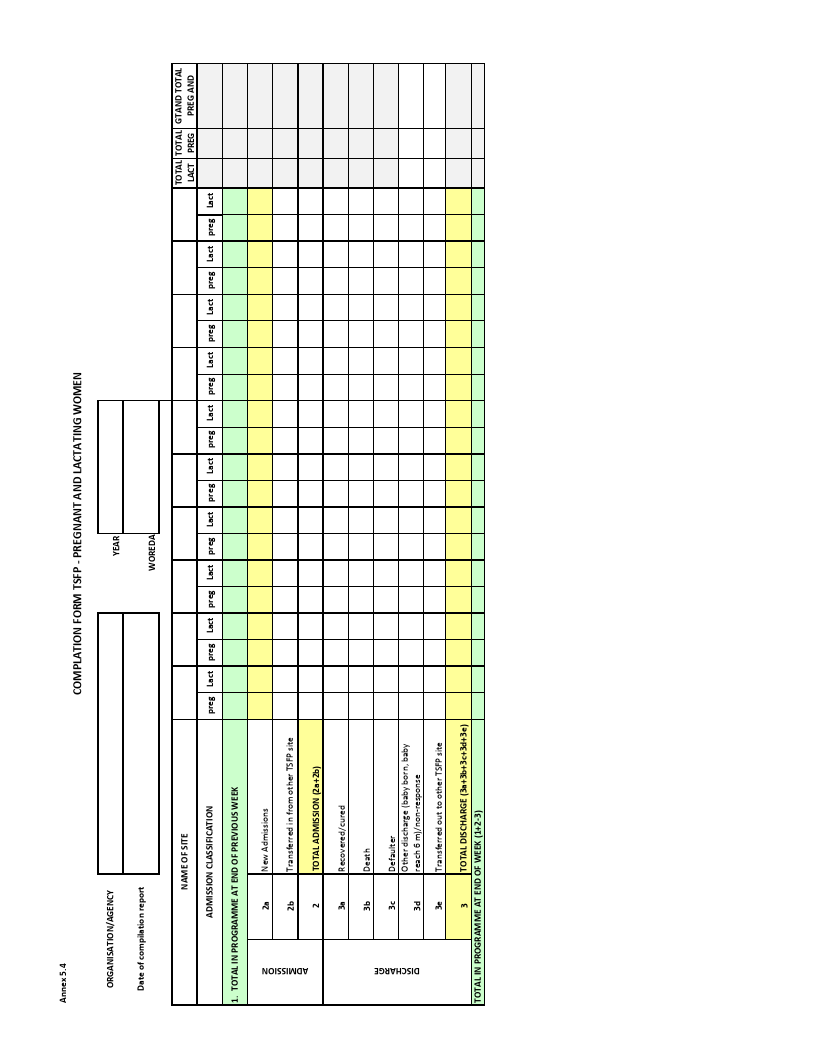

Registration Book: Children 6-59 months and PLW

TSFP Tally and Compilation Sheets

TSFP Monthly Statistics Report & How To Calculate Average Weight Gain, Length Of Stay

TSFP Supervision Checklist

Suggested Equipment and Supplies for TSFP

Stock Card

Taking Anthropometric Measurements: Oedema, MUAC, height/length and weight

WFH % of Median Reference Table (NCHS 1977) & Admission and Discharge Criteria Table

WFH z-score Reference Table for Adults and Adolescents

Referral Form Between TSFP and OTP

How to Prepare CSB

Decision Tree for Nutritional Products

Discharge Table (13%) Target Weight Gain

Discussion of 13% Weight Gain as MUAC Discharge Criteria

Home Visit Form

Post Distribution Monitoring (PDM) Questionnaire

Planning and Analysing Focus Group Discussions (FGD)

CSAS Picture Guide

Guiding Principles on IYCF in Emergencies

Warehouse Management

Glossary of Acronyms

AIDS

ANC

ASRI

BMI

BSFP

CBN

CDC

CHD

CMAM

CSAS

CSB

CTC

CVHW

DHS

DRMFSS

EHNRI

ENCU

ENA

ENI

ENN

EOS

EPI

FBF

FDA

FFI

FGD

FMHACA

FMoH

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

Ante Natal Care

Accelerated Stunting Reduction Initiative

Body Mass Index

Blanket Supplementary Feeding Programme

Community Based Nutrition

Centre for Disease Control and Prevention

Child Health Day

Community Management of Acute Malnutrition

Centric Systematic Area Sampling

Corn-Soy Blend

Community-based Therapeutic Care

Community Volunteer Health Worker

Demographic and Health Survey

Disaster Risk Management and Food Security Sector

Ethiopian Health and Nutrition Research Institute

Emergency Nutrition Coordination Unit

Essential Nutrition Actions

Emergency Nutrition Intervention

Emergency Nutrition Network

Enhanced Outreach Strategy

Expanded Programme of Immunisation

Fortified Blended Food

Food Distribution Agent

Food Fortification Initiative

Focus Group Discussion

Food, Medicine and Health Care Administration and Control Authority

Federal Ministry of Health

v

GAM

GFD

GMP

GoE

GS

HABP

HEP

HEW

HFA

HIV

HTP

IASC

IDP

IEC

IFE

IRT

ITN

IU

IUGR

IYCF

KCAL

LBW

MAM

MAMI

MDG

MoH

MUAC

NCHS

NFI

NGO

NNP

NNS

OTP

PLWHA

PLW

PSNP

RDA

RUF

RUSF

RUTF

S3M

SAM

SC

SD

SFP

SQUEAC

TB

TFP

TFU

TSFP

UNHCR

UNICEF

VAS

WASH

WFA

WFH

WFP

WHO

Global Acute Malnutrition

General Food Distribution

Growth Monitoring and Promotion

Government of Ethiopia

Growth Standards

Household Asset Building Programme

Health Extension Programme

Health Extension Worker

Height-for-Age

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Harmonised Training Package

Inter-Agency Standing Committee

Internally Displaced Population

Information, Education and Communication

Infant Feeding in Emergencies

Integrated Refresher Training

Insecticide Treated Net

International Units

Intra Uterine Growth Retardation

Infant and Young Child Feeding

Kilocalories

Low Birth Weight

Moderate Acute Malnutrition

Management of Acute Malnutrition in Infants

Millennium Development Goal

Ministry of Health

Mid Upper Arm Circumference

National Centre for Health Statistics

Non Food Item

Non-Governmental Organisation

National Nutrition Programme

National Nutrition Strategy

Outpatient Therapeutic Programme

People Living With HIV/AIDS

Pregnant and Lactating Women

Productive Safety Net Programme

Recommended Daily Allowance

Ready-to-Use Food

Ready-to-Use Supplementary Food

Ready-to Use Therapeutic Food

Simple Spatial Survey Method

Severe Acute Malnutrition

Stabilisation Centre

Standard Deviation

Supplementary Feeding Programme

Semi-Quantitative Evaluation and Assessment of Coverage

Tuberculosis

Therapeutic Feeding Programme

Therapeutic Feeding Unit

Targeted Supplementary Feeding Programme

United Nations High Commission for Refugees

United Nations Children’s Fund

Vitamin A Supplementation

Water Sanitation and Hygiene

Weight-For-Age

Weight-For-Height

World Food Programme

World Health Organisation

vi

Definition of Terms

Acute malnutrition/ wasting - measure of “thinness” due to rapid recent weight loss.

Anthropometry - the study and technique of human body measurement. It is used to measure and monitor

nutritional status in an individual or population group. Body measurements include: age, sex, weight,

height, oedema (fluid retention) and mid upper arm circumference (MUAC).

Blanket Supplementary Feeding (BSF) - feeding of all nutritionally vulnerable population irrespective of

nutritional status.

Body Mass Index (BMI) - a number that indicates a person’s weight in proportion to height/length,

calculated as kg/m².

Caregiver – parent or guardian of the malnourished child.

Community Involvement (sometimes referred to as social or community mobilisation) - term used to

cover a range of activities that, help nutrition programme implementers (i.e. nutritionists, managers and

health workers) build a relationship with the community and encourage programme uptake by community

members.

Community-based Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) - international term for timely detection

of severe acute malnutrition in the community (social mobilisation); provision of treatment for those

without medical complications with ready-to-use therapeutic foods or other nutrient-dense foods at home

(OTP) combined with a facility-based approach for those malnourished children with medical complications

(TFU or SC). In some instances/programmes the CMAM also includes TSFP activities.

Community Sensitization - a way to reach out to people in the community and teach the causes, signs and

symptoms of malnutrition, and how to seek treatment opportunities and prevent healthy children from

becoming malnourished.

Community-based Therapeutic Care (CTC) - international term used prior to the CMAM term.

Complementary Feeding - the process starting when breastmilk alone is no longer sufficient to meet the

nutritional requirements of infants and therefore other food and liquids are needed along with breastmilk.

The target age range for complementary feeding is generally 6-24 months even though breastfeeding can

continue beyond 2 years.

Crude Mortality Rate (CMR) - the rate of death in the entire population, including both sexes and all ages.

The CMR can be expressed with difference standard population denominators and for different time

periods, often commonly described as deaths per 10,000 population per month/year.

Emergency Nutrition Intervention (ENI) - programmes set-up to manage malnutrition and to provide food

to a population that does not have sufficient access to or quality of food. Emergency Nutrition

Interventions can also be started in response to other factors such as disease outbreaks in populations with

sufficient access to food.

Evaluation - a process that objectively determines appropriateness, relevance, effectiveness, efficiency and

impact of activities in light of specified objectives.

vii

Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) - breastfeeding while giving no other food or liquid, not even water.

Recommended for infants up to the age of 6 months.

Fortified Blended Food (FBF) - a precooked mixture of cereals and other ingredients such as pulses, dried

skim milk and vegetable oil, which is fortified with micronutrients. Commonly marketed as CSB (+ and ++),

Famix or Unimix.

F-75 - Formula 75 (75kcal/100 ml) is the milk based diet recommended by WHO for the stabilisation of

children with SAM with in inpatient care (those with medical complications and/or no appetite).

F-100 - Formula 100 (100kcal/100 ml) is the milk based diet recommended by WHO for the nutrition

rehabilitation of children with SAM after stabilisation in inpatient care, now is generally replaced by RUTF.

Global Acute Malnutrition (GAM) - a population indicator that provides an aggregate of moderate and

severe malnutrition, i.e. ≤-2 Z-scores and oedema. GAM is divided into moderate and severe acute

malnutrition (GAM = MAM+SAM).

Inpatient Therapeutic Care - severely malnourished patients admitted to inpatient facility for treatment

(TFU or SC).

IYCF - describes the feeding of infants and young children (usually 0-24 months).

Kwashiorkor - bilateral pitting oedema (nutritional oedema) that is a clinical indicator for SAM. Oedema is

the excessive accumulation and abnormal infiltration of serous fluid in connective tissue or in a serous

cavity. Classified into 3 grades; + mild (both feet, can include ankles), ++ moderate (both feet, lower legs,

hands or lower arms); +++ severe (generalized oedema over whole body including arms and face).

Malnutrition - a state in which the physical function of an individual is impaired to the point where s/he

can no longer maintain adequate bodily performance processes.

Marasmic-Kwashiorkor – a combination of both maramus and kwashiorkor.

Marasmus - severe weight loss and muscle mass leaving ‘skin and bones’. Appearance can manifest as ‘old

man face’ and ‘baggy pants’.

Moderate Acute Malnutrition - description of malnutrition level; persons with MAM have higher morbidity

and mortality risks. In Ethiopia the definition encompasses children 6-59 months with < -2 to ≥-3 z-scores

and/or MUAC ≥ 11.0 to < 12.0 cm; and PLW with MUAC < 23.0 cm. For MAM classifications for infants,

older children and adults in Ethiopia, please refer to Table 3 on page 19.

Monitoring - periodic oversight of the implementation of an activity which seeks to establish the extent to

which input deliveries, work schedules and targeted outputs are proceeding according to plan.

MUAC – Low MUAC is an indicator for wasting. For a child 6-59 months, MUAC < 11.0 cm indicates severe

wasting or SAM, MUAC ≥ 11.0 to < 12.0 cm indicates moderate wasting or MAM. For PLW, MUAC < 23.0 cm

indicates MAM. For adults with HIV/AIDS (or other chronic diseases), MUAC ≥ 18.0 to < 23.0 cm indicates

MAM. MUAC is a better indicator of mortality risk associated with acute malnutrition than WFH.

NCHS/WHO Reference - the 1977 NCHS/WHO growth reference, which is based on the weights and heights

of a statistically valid population of healthy infants and children in the United States, was previously widely

used to assess, monitor and evaluate the nutritional status of individual children or groups of children.

Many countries have now moved to the use of the new WHO Growth Standards (2006), see below.

viii

Nutrition - study of food and its nutrients; its functions, actions, interactions and balance in relation to

health and disease.

Nutrition Education – process of imparting knowledge, designed to improve people’s attitude, habits,

behaviour, customs and beliefs that are related to food consumption

Outpatient Therapeutic Programme (OTP) - programme run from a health centre or health post offering

outpatient care to severely malnourished cases who have appetite and who do not have any medical

complications (this group usually represents > 90% of all the SAM cases). At admission, children receive a

medical check to determine if they warrant direct referral to the nearest inpatient TFU. If they are well

enough to be treated as an outpatient they receive systematic treatment and a ration of RUTF. Patients are

seen on a weekly or fortnightly basis, but carers are encouraged to return to the OTP if the child’s condition

deteriorates during that time. The average length of stay in OTP is 4-8 weeks.

Prevalence Rate - the proportion of the population that has the health problem under study (e.g. the

prevalence of GAM).

Ready-to Use Foods (RUFs); Ready-to use Supplementary Food (RUSF) and Ready-to Use Therapeutic

Food (RUTF) - energy dense, mineral and vitamin enriched food that does not require cooking or

preparation or dilution with water and can be eaten directly from the packet. RUTF has been specifically

developed for the recovery of severe acute malnutrition at home, while RUSF is for the recovery of

moderate acute malnutrition.

Recommended nutrient intake (RNI) - the daily intake which meets the nutrient requirements of almost all

(97.5%) apparently healthy individuals in an age- and sex-specific population.

Selective Feeding Programmes – therapeutic (for severely malnourished) and supplementary (for

moderately malnourished).

Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) - description of malnutrition level encompassing children 6-59 months

with < -3 z-scores, and/or MUAC < 11.0 cm, and/or bilateral pitting nutritional oedema. Persons with SAM

have higher morbidity and mortality risks.

Sphere Project - was launched in 1997 by a group of humanitarian NGOs, the Red Cross and Red Crescent

movement. The Sphere humanitarian charter and minimum standards in disaster response, 3rd edition

(2011) has just been released; providing a set of recommendations that humanitarian projects should aim

to meet.

Standard Deviation (SD) or z-score - the deviation of the anthropometric value (weight, height etc.) for an

individual from the median value of the reference population.

Stunting - or chronic undernutrition, is a form of undernutrition that is defined by a height-for-age (HFA) z-

score below two SDs of the median WHO standards. Stunting is a result of prolonged or repeated episodes

of undernutrition often starting before birth. This type of undernutrition is best addressed through

preventative maternal health programmes aimed at pregnant women, infants, and children under age 2.

Programme responses to stunting require longer-term planning and policy development.

Supplementary Feeding Programme (SFP) - provision of an additional food ration for moderately

malnourished individuals through a ‘targeted SF’; or to the most nutritionally vulnerable groups (regardless

of nutritional status) through ‘blanket SF’.

Targeting - a method of delivering goods (such as food assistance) and/or services to a selected group of

individuals or households, rather than to every individual or household in the population.

ix

Therapeutic Feeding Programme (TFP) - combination of inpatient (TFU) and outpatient (OTP) therapeutic

feeding for the treatment of severe acute malnutrition.

Therapeutic Feeding Unit (TFU) - units in hospitals and health centres offering inpatient care to the

severely malnourished cases with complications and/or lack of appetite. If OTP is not available in the

catchment area, TFU offers full inpatient care with Phase 1, Transition Phase and Phase 2 with an average

length of stay of 2-3 weeks. When OTP is available in the catchments area, only the complicated severe

cases as defined by a lack of appetite and the presence of medical complications are admitted in TFU.

Usually, patients would only stay as long as they required Phase 1 treatment (2-7 days) and then would

progress to outpatient care.

Triage of Acute Malnutrition - Refers to the selection/ sorting/classification of cases of acute malnutrition

presented to fast track treatment and increase survival rates.

Undernutrition - Is a consequence of a deficiency in nutrient intake and/or absorption in the body. The

different forms of undernutrition that can appear isolated or in combination are acute malnutrition

(bilateral pitting oedema and/or wasting), stunting, underweight (combined form of wasting and stunting),

and micronutrient deficiencies.

Underweight - Underweight is a composite form of undernutrition including elements of both stunting and

wasting and is defined by a weight-for-age (WFA) z-score below 2 SDs of the median (WHO standards). This

indicator is commonly used in growth monitoring and promotion (GMP) and child health and nutrition

programmes aimed at the prevention and treatment of undernutrition.

Vulnerable Groups – Groups of people who are ‘at risk’ of malnutrition, which vary in characteristic but are

often defined by age, sex, ethnicity and location; can also include those with disabilities and stigmatised

illnesses, such as mental ill-health and displaced persons such as refugees or migrant workers

WHO Growth Standards (WHO GS 2006) - Developed using data collected in the WHO Multicentre Growth

Reference Study in Brazil, Ghana, India, Norway, Oman, and the United States between 1997 and 2003 to

generate new curves for assessing the growth and development of children from birth to five years of age

under optimal environmental conditions. They are intended to be used to assess children everywhere,

regardless of ethnicity, socioeconomic status and type of feeding.

Z-score - Indicates how far a measurement is from the median – also known as the standard deviation (SD)

score. The reference lines on the growth charts (labelled 1, 2, 3, -1, -2, -3) are called z-score lines; they

indicate how far the measurement is above or below the median (= z-score of 0).

x

Introduction

Current health and nutrition situation in Ethiopia

Ethiopia is the third most populous country in Africa with an estimated population of 79.5 million, of which

approximately 11 million are children under-5.1 The health situation in Ethiopia is generally poor; a

reflection of widespread poverty, limited employment opportunities, low income levels, high population

pressure, low education levels (especially among women), inadequate access to clean water and sanitation,

high rates of migration and poor access to health services. The recent National Nutrition Survey (2010)

confirmed that maternal and child feeding practices and knowledge of ‘healthy behaviours’ remain at sub-

optimal levels.2

Ethiopia’s long and continuing history of food insecurity is attributed to erratic rainfall and/or the complete

failure of rains, degraded land, archaic and inefficient farming practices and regular pest infestations,

among other factors. As a result, every year millions of people in rural Ethiopia are in need of support in the

form of food aid, nutrition support, health, water supply and sanitation, shelter and other emergency

inputs. With more than 80% of the population relying on subsistence agriculture as their primary livelihood,

they are dependent on the success of two annual rainy seasons to secure nearly all their food needs for the

year. As such, they are particularly vulnerable to climatic shocks and their ability to recover from those

shocks is limited. Over the past few years some communities have faced considerable hardships, as one or

other, or both of the two annual rains have failed and pest infestation has been high, causing crop failures

across many areas of the country and intensifying the cumulative vulnerability of communities

The consequence of Ethiopia’s poor health situation, sub optimal caring practices and continuing food

insecurity (which can regularly develop into more severe food crises), is that malnutrition rates among

children remain at unacceptably high levels; the prevalence of Global Acute Malnutrition (GAM) at the

national level is estimated to be 11% (moderate and severe), with 47% of children suffering from chronic

malnutrition. By now it is very well understood that much of childhood morbidity and mortality is rooted in

malnutrition. While it is encouraging that Ethiopia’s under-5 mortality rate has decreased in recent years

from 169/1,000 to 123/1,000 live births, this figure still represents 389,000 under-5 deaths annually.3

The importance of achieving good nutritional status for vulnerable groups is fundamental, not only to avoid

the short-term consequences of increased morbidity and mortality, but also to avoid potential longer-term

economic consequences that have been identified. Undernourished infants and children, who manage to

survive may be subject to longer-term impairment. Furthermore, they are more likely to grow into shorter

adults, to have lower educational achievements and, for women, more likely to subsequently give birth to

smaller infants themselves, thus perpetuating an intergenerational cycle of undernutrition. Prevention of

maternal and child undernutrition is therefore of critical importance that will benefit not only the present

generation, but also their children.4

1 Population Projection (2010) according to the Ethiopia Census 2007. Central Statistics Agency.

2 The National Nutrition Survey, 2010. Ethiopian Health and Nutrition Research Institute.

3 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey, 2005. Central Statistics Agency. Preliminary results from the EDHS 2011 suggest that

the U5 mortality rate has reduced to 88/1,000 live births

4 Black, R., Allen, L. H., Bhutta, Z. A., Caulfield, L. E., De Onis, M., Ezzati, M., Mathers, C., and Rivera, J. For the Maternal and

Child Undernutrition Study Group. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. The

Lancet. Published online Jan 17 2008. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0

1

In response to the continuing high levels of malnutrition, the Government of Ethiopia (GoE) developed the

National Nutrition Strategy during 2008, to be implemented through the National Nutrition Programme

(NNP). The objective is better harmonization and coordination of the various approaches to manage and

prevent malnutrition. The NNP is currently a 10 year initiative, aiming to reduce the levels of stunting,

wasting, underweight and Low Birth Weight (LBW) infants, thus contributing to Ethiopia’s efforts to reach

the relevant Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) by 2015. Its first phase spans five years (2008-2013)

and consists of two main components: a) ‘Supporting Service Delivery’ which includes ‘increased access for

the management of Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM)’, and b) ‘Institutional Strengthening and Capacity

Building’.

In efforts to further expedite improvements in nutrition indicators, the GoE has recently developed a

number of initiatives to combat malnutrition and work toward reaching the MDGs, which include the

Accelerated Stunting Reduction Initiative (ASRI), Food Fortification Initiative (FFI) and enhancing linkages

between the NNP and the Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP).

Box 1: The Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP)

The PSNP focuses support continuously on selected households over several years and has an

explicit objective of beneficiaries eventually graduating. The PSNP is the largest social safety

net programme in Sub-Saharan Africa with plans for it to be complemented by the Household

Asset Building Programme (HABP)

The PSNP is currently reaching 7.57 million chronically food insecure people through two

components: public works (80%) and direct support (20%). This remuneration enables

households to meet their food gaps (through provision of food or cash), in order that they are

not forced to sell productive assets, when faced with periodic food shortages or other shocks.

Current MAM situation in Ethiopia

The 2005 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) identified that 11% of children 6-59 months in Ethiopia

were wasted; a situation that has remained unchanged since the first DHS conducted in 2000. A number of

approaches have been employed over recent years to address MAM, summarised below.

MAM in Ethiopia is currently detected and treated via three food-based programmes:

1. The Ethiopian government has been implementing the Enhanced Outreach Strategy Targeted

Supplementary Feeding (EOS/TSF) programme or Child Health Days (CHD), which conducts

screening exercises (6-monthly and 3-monthly, respectively) in 168 chronically food insecure

woredas and includes provision of TSF rations for identified MAM individuals. Selected beneficiaries

[drawn from under-5 children and Pregnant and Lactating Women (PLW)] are issued with a ration

card that is presented to receive 3-monthly TSFP rations. In addition to screening, additional

promotive/preventative services are provided every 6 months, of vitamin A supplementation (VAS)

and de-worming. The EOS is in the process of transitioning into the activities of the routine CHDs

that are managed by the Health Extension Workers (HEWs) every 3 months; as such MAM

treatment will be provided as part of routine health services in food insecure areas of the country.

2. During times of deteriorating and/or acute nutritional situations (as defined and guided by the

DRMFSS 'hot-spot' classification of woredas as food insecure, with raised malnutrition rates), a

smaller MAM caseload is detected and treated, usually through Non-Governmental Organisations

(NGOs) Targeted Supplementary Feeding Programmes (TSFPs), set up in selected woredas. These

programmes act as a complement to on-going Therapeutic Feeding Programmes (TFPs). The TSFPs

2

are characterised by rigorous nutritional monitoring, active case finding and usually bi-weekly

distributions. However, it is important to note that these NGO TSFPs are generally short-term

operations and have limited coverage across this vast country.

3. While not identified by their nutritional status, young children and pregnant women are included in

beneficiary lists of communities receiving relief food to benefit from an extra ration of highly

fortified Corn Soya Blend (CSB)5. This intervention is embedded in the DRMFSS sector of the

Ministry of Agriculture and is also addressing MAM to some extent.6

While we know that MAM treatment programmes work, there is considerable interest to move away from

the ‘food bias’ when treating MAM and the international community has been raising questions about the

effectiveness of traditional SFPs.7 However, as yet there is limited evidence available for what type of non-

food interventions might be most appropriate to both prevent and treat MAM in the Ethiopian context. In

some countries, cash transfers are being targeted to malnourished populations, although it is recognised

that this alternative might need to be piloted in the Ethiopian context alongside the ongoing

implementation of the PSNP, which already provides cash transfers to large sections of the population.

Additionally, cash transfers intended to treat MAM could face some challenges in areas of Ethiopia, where

there might be limited purchasing availability in the markets for sufficiently nutritious food.

Due to the interest in other (and potentially more effective) approaches, some organisations are currently

reviewing traditional SFP programming e.g. the Centre for Disease Control (CDC) ‘grey literature’ review

and the University of Westminster and Emergency Nutrition Network (ENN) review of evidence for the

effectiveness of interventions during emergencies. It is possible that ‘new and improved’ thinking or

alternative methods of programming might be proposed in the near future. It is therefore recommended

that these guidelines are viewed as ‘living document’, subject to revision as new evidence and best

practices emerge.

The aim of these guidelines

These guidelines are intended for use by all health and nutrition staff from government, agencies and

organisations involved in nutrition related activities in Ethiopia. The purpose of the guideline is to define

basic concepts and criteria related to the planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of

nutritional interventions aimed at treating and/or preventing Moderate Acute Malnutrition (MAM) and to

describe locally appropriate and internationally acceptable standards for MAM treatment programmes, as

well as overall intervention management.

These guidelines focus on the implementation of Supplementary Feeding Programmes (SFPs) in emergency

contexts, to complement the programme implementation manual of the EOS/TSF that guides the ongoing

programmes to identify and treat MAM. They also highlight the importance of increased awareness of

infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) and maternal nutrition; in order to reduce the incidence of MAM in

Ethiopia through comprehensive programming, as outlined in Ethiopia’s National Nutrition Programme

(NNP). In response to requests from the MAM TWG to provide the latest international information, at times

these guidelines veer from technical guidance on known interventions, to discussion of some of the

outstanding questions that are arising during the implementation of programmes to address MAM.

These guidelines should be used in conjunction with the Emergency Nutrition Intervention (ENI) Guideline,

2011, and the Guidelines for the Treatment of Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) in Ethiopia, 2007, endorsed

by the Ministry of Health.8

5 The more enriched product of CSB+ is known as ‘super cereal’. CSB++ is now known as ‘super cereal plus’

6 Concept note for the Management of MAM. Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health, 2010.

7 Navarro-Colorado, C., Shoham, J., Mason, F. Measuring the effectiveness of Supplementary Feeding Programmes in Emergencies.

Working Paper HPN Network Papers 63, August 2008.

8 Protocol for the Management of Severe Acute Malnutrition, Ethiopia, Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH), March 2007.

3

Chapter 1. Overview and classification of malnutrition

1.1 Types of malnutrition

The nutritional requirements of individuals vary at different stages of life and depend on a number of

factors including age, sex and current health status of the individual. Nutritional requirements will also

depend on:

differing physiological conditions, such as pregnancy and breastfeeding

environmental conditions, such as temperature

varying levels of physical activity

There are two categories of nutrients needed by the body:

1. Macronutrients - that provide the energy required for growth and replacement of cells, which are

required in large amounts and include protein, carbohydrate and fat

2. Micronutrients - which ensure the healthy functioning of organs and body processes. These are

required in much smaller amounts and include vitamins and minerals

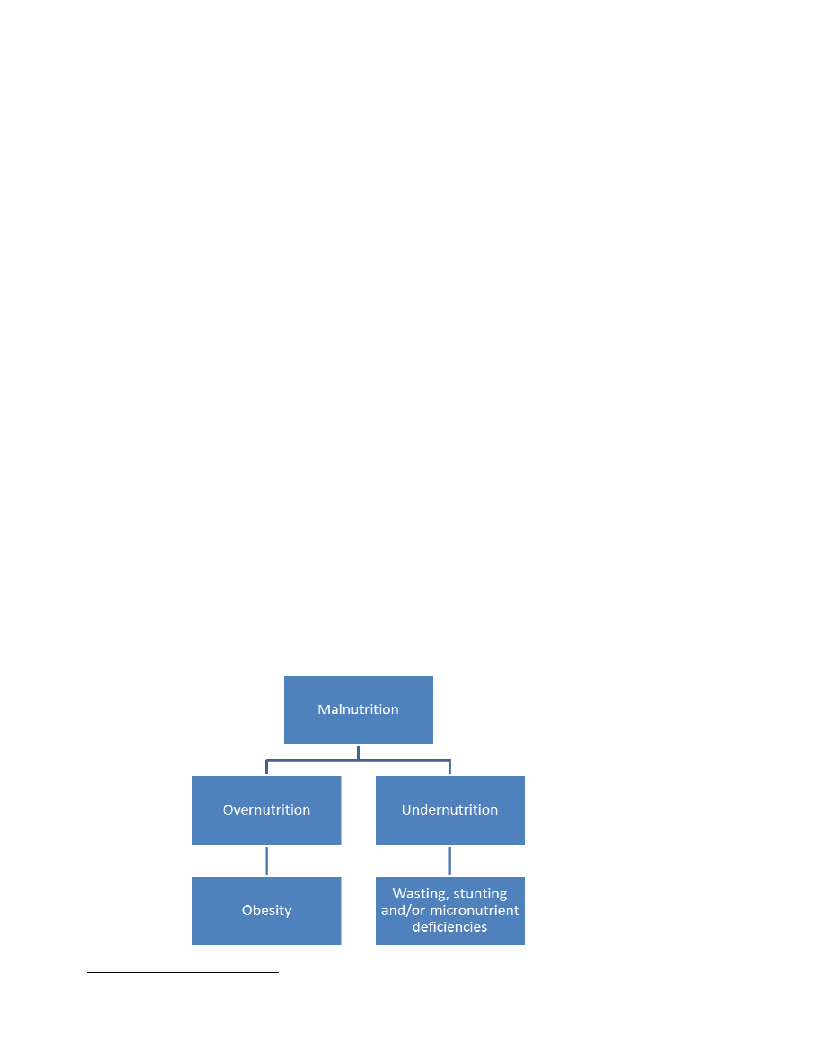

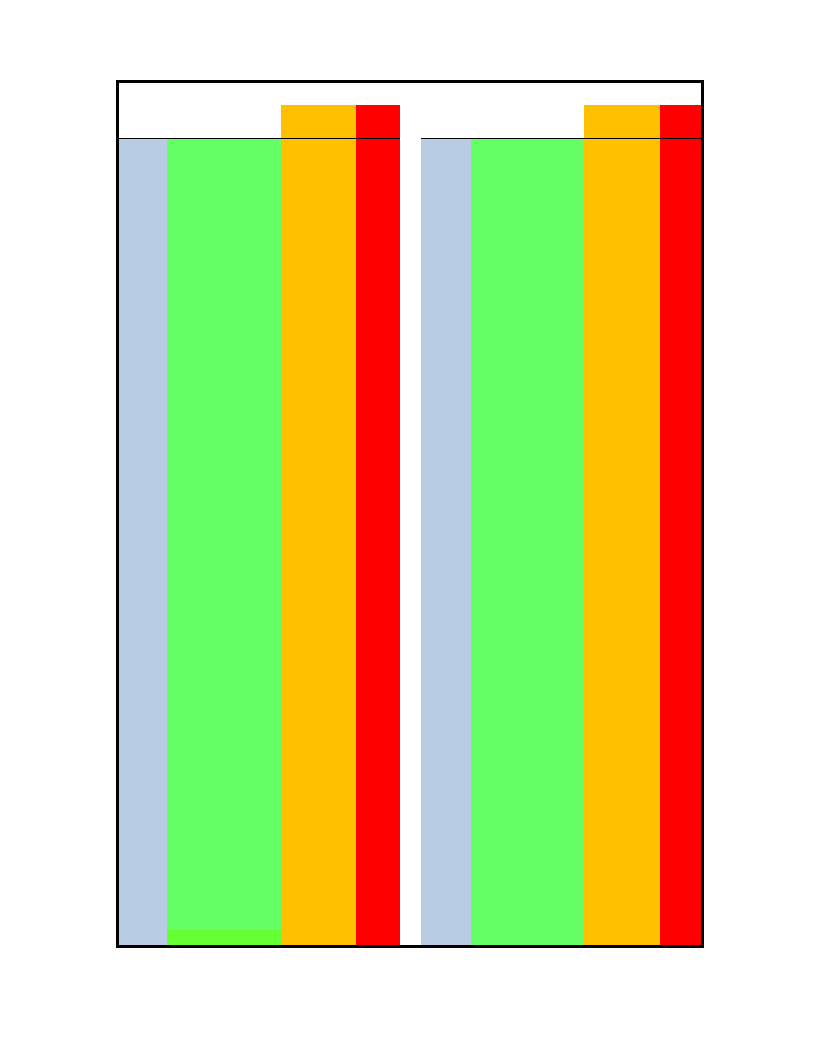

Malnutrition can exist in two forms as outlined in Figure 1 below; overnutrition and undernutrition.9 In

Ethiopia the most common form of malnutrition is undernutrition, which can manifest as wasting, stunting

and/or deficiencies of essential vitamins and minerals (collectively referred to as micronutrients).

Undernutrition generally results from a complex web of interactions, from the molecular and

microbiological level of the individual, to the cultural and socioeconomic features of societies.10

Figure 1: Types of Malnutrition

9 In this guideline unless otherwise indicated, the term ‘malnutrition’ refers to undernutrition in the form of wasting.

10 Heikens, G. T., Amadi, B. C., Manary, M., Tollins, N., and Tomkins, A. Nutrition interventions need improved operational

capacity. The Lancet. Published online Jan 17 2008. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0

4

The three main types of undernutrition are known as acute malnutrition (wasting), chronic malnutrition

(stunting) and micronutrient deficiency.

1. Chronic malnutrition or ‘stunting’ (individuals whose height is below the average expected height

for their age) - is generally a result of prolonged or repeated episodes of undernutrition that often

starts before birth. Stunting is strongly associated with poverty, poor health and impaired physical

and mental development. Stunting can be reversed through ‘catch up growth’ until 2 years of age;

after which it is irreversible.

2. Acute malnutrition or ‘wasting’ [a measure of thinness defined by Weight-For-Height (WFH) or Mid

Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) measurements] - is characterized by rapid weight loss usually

due to illness and/or reduced food intake. Wasting can be reversed, however it is of particular

concern during emergency situations because it can quickly lead to excess morbidity and mortality.

Acute malnutrition leads to changes in the body related to cellular composition, tissue and organ

functions. Acute malnutrition can either present itself as severe or moderate and can result from

type II nutrient deficiencies (see below)

3. Micronutrient deficiencies - individuals can have a deficiency of either Type I or type II nutrients.

a. Type I nutrients are those required for adequate functioning of the body, such as iron,

vitamin A, iodine, etc. These nutrients regulate hormonal, immunological, biochemical and

other bodily processes. While these deficiencies can cause major illness and increased risk

of mortality, anthropometric measurements (e.g. height and weight) can be normal,

although it is common for stunted or wasted individuals to also have some degree of

micronutrient deficiency.

b. Type II nutrients are the growth nutrients required to build new tissue e.g. nitrogen,

essential amino-acids, potassium, magnesium, sulphur, phosphorus, zinc, sodium, etc.

Deficiencies will result in the failure to grow, to repair tissue that is damaged, to replace

cells that rapidly turn-over (e.g. intestine and immune cells) or to gain weight after an

illness, which can lead to an increase in the risk of stunting and/or wasting.

1.2 Causes of malnutrition

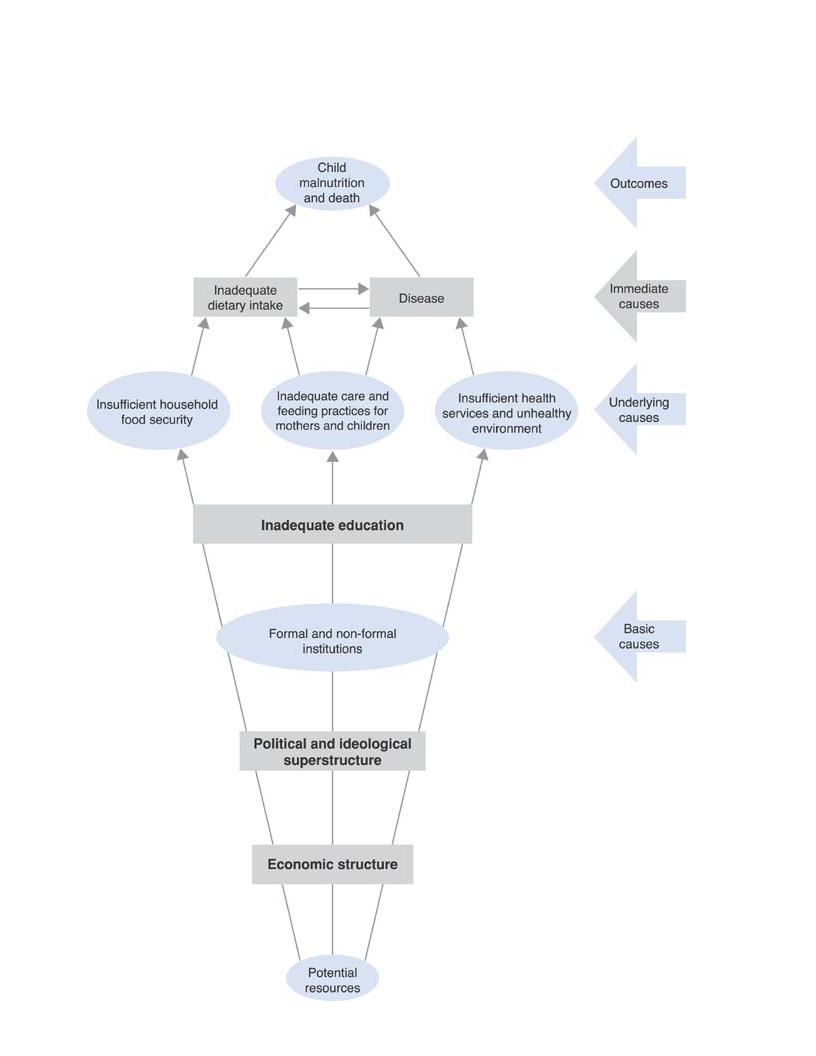

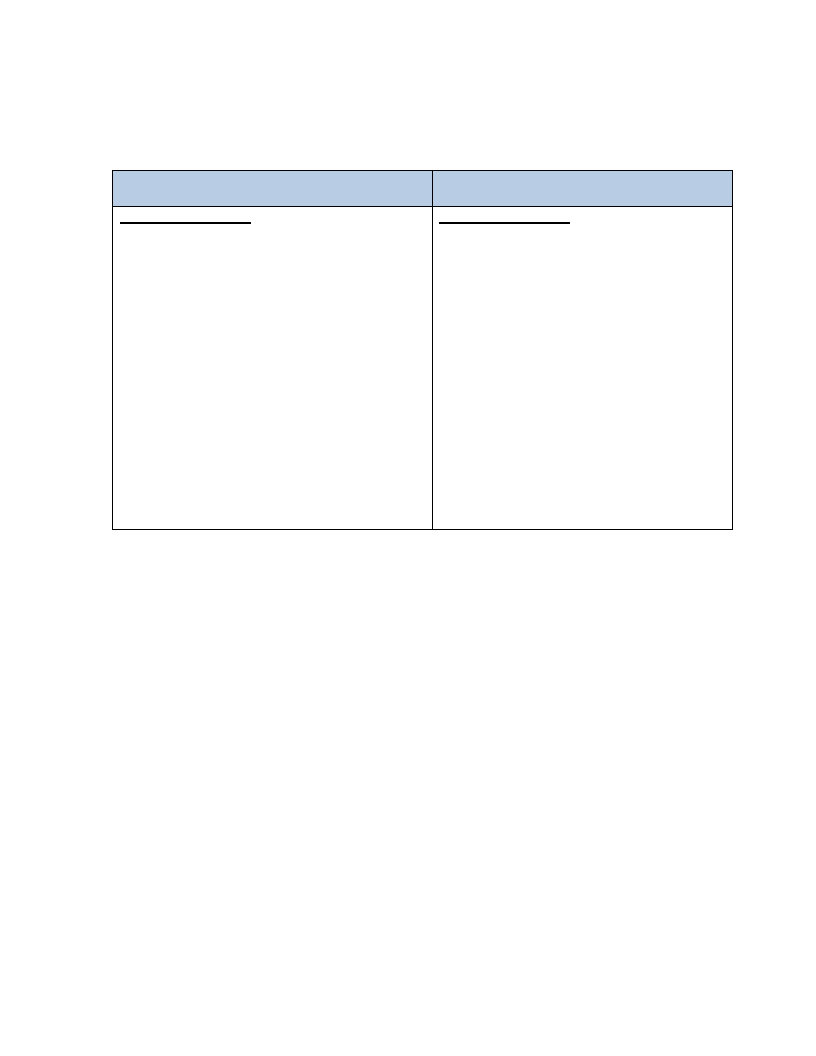

Figure 2 below describes the three layers of the determinants of nutritional status;

1. Immediate - which act on the individual

2. Underlying - which influence households and communities

3. Basic - which act on entire societies

5

Figure 2: UNICEF conceptual framework for the determinants of nutritional status

6

1. Immediate Causes

These include inadequate dietary intake and infection or disease. Malnutrition is often exacerbated by

a vicious cycle between these two factors. Inadequate food intake can lead to a higher risk of infection

or disease, and conversely disease can lead to inadequate food intake. In the Lancet series (2008) Black

et al, summarised the effects of the deadly relationship between infection and undernutrition by

stating that:

“substantially more children die as a result of the synergy between infectious diseases and

undernutrition than from the direct sequelae of the nutritional conditions themselves.” 11

Nine out of ten child deaths in Ethiopia are due to only five conditions: pneumonia, malaria, diarrhoea,

neonatal problems and measles. Approximately 57% of these deaths are related to a weak physical

state due to malnutrition (three-quarters of these deaths result from mild to moderate malnutrition).12

2. Underlying Causes

The main underlying causes of malnutrition include shocks, such as drought, flooding, etc.; household

food insecurity, inadequate social and care environment, inadequate access to health services and

environmental factors, such as poor water and sanitation facilities.

3. Basic Causes

The basic causes of malnutrition include the country’s social, economic and political situation, for

example, the formulation and implementation of policies to address issues such as lack of capital

(financial, human, physical, social, agro-ecological, technical).

1.3 Identification of acute malnutrition using WHO growth

standards (2006)

The World Health Organisation (WHO) undertook a comprehensive survey in the early 1990’s to review the

existing National Centre for Health Statistics (NCHS) 1977 reference values and develop more appropriate

standards for use with a wider range of children from a variety of ethnic backgrounds, in developing and

developed countries. The outcome of this survey was the development of new growth standards that

describe how children should grow when their nutritional needs are fully met. These child growth standards

support the notion that given the same environmental conditions, growth potential is independent of

ethnic origin; therefore these standards can apply in any country.

The new growth standards use the same cut-off points for weight-for-height, weight-for-age, and height-

for-age z-scores, although the international recommendations for cut-off points for mid-upper arm

circumference (MUAC) measurement was increased from a MUAC <11cm to <11.5cm for SAM diagnosis.

The MUAC cut-off for MAM diagnosis remained the same at <12.5 cm.13

11 Black, R., Allen, L. H., Bhutta, Z. A., Caulfield, L. E., De Onis, M., Ezzati, M., Mathers, C., and Rivera, J. For the Maternal and

Child Undernutrition Study Group. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. The

Lancet. Published online Jan 17 2008. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0

12 UNICEF and IFPRI coordinated effort, 2005. An Assessment of the causes of Malnutrition in Ethiopia: A contribution to the

formulation of a National Nutrition Strategy for Ethiopia (Background Papers)

13The FMoH has endorsed the MUAC cut-offs for children 6-59 months in Ethiopia as follows: SAM < 11.0 cm;

MAM ≥11.0 to < 12.0 cm. See section 2.3.2.5 for further details of admission criteria

7

Studies have shown that the changes in growth standards and cut-off points have potential implications on

the numbers of children eligible for admission to selective feeding programmes (especially for SAM, to a

lesser degree for MAM).14 15 16 It is therefore advisable to introduce them systematically so as not to

overload the system. With the introduction of the new growth standards, intense nation-wide training

should be conducted for all staff involved in the treatment of acute malnutrition.

When adopting the new growth standards, selective feeding programmes must be prepared for an increase

in case load by ensuring:

• Staff numbers in health facilities are adequate

• Facility staff are trained on MAM procedures, reporting, stock management, etc.

• Stock capacity at federal, regional, zonal and woreda levels are secured to prevent pipeline

ruptures

1.3.1 Identification of Weight for Height Measurement (WFH) ratio using

the reference tables

When a child's WFH is assessed, the child's weight is being compared to a reference weight for a child of

the same height. The reference weights for each height are known as the WHO reference values. The

reference values are used to assess or compare individual or population nutritional status.

The method by which a child or group of children is compared to the reference is known as "standard

deviation (SD)" or more commonly, "z-score". The z-score or SD describes how far a child's weight is from

the median weight of a child at the same height in the reference population.

The z-score is a more sensitive descriptor than either "percentiles" or "percentage of the median" so its use

implies that more children who are actually malnourished are identified. In addition to MUAC

measurements, to assess malnutrition, z-score or SD is used.17

For assessment of malnutrition in adolescents or adults, see section 2.3.2.5.3.

Health workers should use the WFH Reference Tables

for Girls and Boys in annex 1 to quickly identify if a child

is acutely malnourished or not.

14 Myatt, M., and Duffield, A. (2007) Assessing the impact of the introduction of the World Health Organisation (WHO) growth

standards on the measured prevalence of acute malnutrition and the number of children eligible for admission to emergency feeding

programmes. Background paper

15 de Onis, M., Onyango, A. W., Borghi, E., Garza, C., Yang, H. (2006) Comparison of the World Health Organisation (WHO) child

growth standards and the National Centre for Health Statistics/WHO international growth reference: implications for child health

programmes. Public Health Nutrition 9: 942-947

16 Seal, A., and Kerac, M. (2007) Operational implications of using the 2006 World Health Organisation growth standards in

nutrition programmes: secondary data analysis. British Medical Journal. DOI:10.1136

17 For programmes that are not yet implementing the WHO GS (2006), instead are using NCHS (1977) ‘percentage of the median’

reference values, the WFH reference tables are provided in annex 11.

8

1.3.2 Identification of malnutrition using MUAC

MAM in children 6-59 months (girls and boys) is

classified as a MUAC measurement of

≥ 11.0 to < 12.0 cm

MUAC tapes are portable, simple to use with minimal training and the colour coding ensures that

beneficiaries (or their caregivers) can easily understand why they have been included in a programme, or

not. MUAC is also the best predictor of mortality, an important fact for any child survival programme.18

However, the accuracy of MUAC measurements [especially those taken during the Enhanced Outreach

Strategy (EOS) nutrition screening] has frequently been questioned. Poor measurements can result in poor

targeting of the nutrition intervention, that is, inclusion of children in the TSFP who may not need nutrition

support and/or exclusion of children who do need nutrition support.

Problems generally arise with insufficient monitoring of programmes; food is a valuable commodity, and it

is all too easy to pull the MUAC tape a ‘bit tight’ to ensure the individual is included in the programme,

particularly if the measurer is under some pressure to include them (e.g. they are known personally to the

worker conducting the screening). It is therefore extremely important to ensure that the measurements are

taken accurately at health facilities or distribution sites, to ensure that only those individuals who fit the

admission criteria and can be admitted to the programme.

1.4 Information sources that can provide information on the need

to establish MAM treatment emergency interventions

MAM is treated in food insecure areas of Ethiopia through routine ongoing activities, such as the TSF/EOS

(as part of the quarterly CHD activities, refer to EOS/TSF implementation manual). However, in times of

heightened food insecurity emergency nutrition interventions might be required. For further information

on sources that can provide evidence on the need to establish emergency nutrition interventions, please

refer to the Ethiopia Emergency Nutrition Intervention (ENI) guideline, 2011.

18 Myatt, M., Khara, T., and Collins, S. A review of methods to detect cases of severely malnourished children in the community for

admission into community-based therapeutic programmes. Food and Nutrition Bulletin. Vol 27. No 3 (Suppl). 2006:S7-23.

9

Chapter 2. Supplementary Feeding Interventions

2.1 Description of supplementary feeding

At present the most common interventions for the management of MAM are Supplementary Feeding

Programmes (SFP). Supplementary feeding is the provision of nutritious rations to vulnerable children

(usually classified at < 5 years) or those with special dietary needs (e.g. pregnant and lactating women,

individuals with HIV/AIDS, etc.). SFPs also provide vital links to ongoing SAM treatment programmes. In

most situations, SFPs are implemented in order to prevent excess mortality among vulnerable groups. SFPs

can either be blanket or targeted and aim to supplement the energy and nutrients missing from the diet

due to various reasons.

During emergency situations, SFPs should be a short-term measure and not necessarily be seen as a means

of compensating for inadequate household food security.19 A significant and continued reduction in the

prevalence of malnutrition is likely only if an SFP is implemented alongside adequate General Food

Distributions (GFD), and/or is well aligned with the PSNP. The recently endorsed National Guidelines on

Targeting Relief Food Assistance (2011) states:

“In areas where nutritionally-targeted interventions such as TSF or CMAM are in operation, the

households of individuals who are registered for such nutritional support should automatically be

included in the registration for GFD. That is, current acute malnutrition should be an inclusion criterion

for general rations. All international experience shows that supplementary feeding is only effective

when the household has adequate access to basic foods.

In PSNP woredas, similarly, no household should be excluded from nutritional programmes (e.g. TSF,

CMAM or BSFP) on the grounds that they are already receiving support from the PSNP. Overlaps

between these programmes at the household level are desirable and represent effective targeting of

complementary assistance types.”20

2.1.1 Objectives of setting up an SFP

It is vital that the objectives of commencing and setting up the programme are well defined at the start of

the programme and are understood by all partners.

1. To reduce the risk of mortality and morbidity associated with MAM

2. To rehabilitate at-risk individuals to prevent deterioration into MAM (blanket SFP) and moderately

malnourished individuals to prevent deterioration into SAM (targeted SFP)

3. To provide a ‘protection ration’ for individuals discharged from therapeutic feeding programmes

and thus prevent relapse into SAM

4. To rehabilitate PLW who are at-risk or moderately malnourished to improve maternal nutritional

status and minimise the risk of infants born with low birth weight

5. To provide nutritional/health education messages for beneficiaries or caregivers and hence

increase awareness on optimal child feeding practices and appropriate health seeking behaviours

19 A toolkit for addressing nutrition in emergency situations. IASC Global Nutrition Cluster, UNICEF, New York, NY, 2008

20 National Guidelines on Targeting Relief Food Assistance. Ministry of Agriculture (Disaster Risk Management and Food Security

Sector), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2011

10

2.2 Planning the intervention

MAM is treated in food insecure areas of Ethiopia through routine ongoing activities, such as the TSF/EOS

(as part of the quarterly CHD activities). However, in times of heightened food insecurity emergency

nutrition interventions might be required.

Prior to any emergency intervention, discussion must be held with local authorities to discuss and

determine the methodology, size, location and other important features of the proposed programme.

Wherever possible, programmes must be run within existing health structures/facilities. SFPs are usually

implemented through a large number of decentralised sites, the number of which will depend on the area,

terrain, density of population, expected number of beneficiaries, etc. The exit strategy of any programme

must be clearly identified and communicated prior to implementation.

2.2.1 Staff

The routine treatment of MAM through the EOS/TSF is currently managed at community level during the

quarterly CHDs by the HEWs, with support from the Food Distribution Agents (FDAs).

During times of heightened food insecurity, emergency SFPs might be needed. When these programmes

are required, it is vital to discuss the aims and objectives of the programme with local officials from the

start, such as woreda Administrators. It is also essential to have local authority representatives, e.g. kebele

Chairpersons, attending distribution activities in order to ensure that the operation runs smoothly and to

facilitate liaison with the community. Local government personnel are essential for good communication

between programme implementers and the community, for example, clarity regarding which vulnerable

groups the programme is targeting, passing messages for which days distributions will be held, any changes

to the schedule, etc.

Emergency SFPs are encouraged to use whatever capacity is already present in the community e.g. existing

FDAs, who will have prior knowledge and experience with screening, health education, etc. Additional

numbers and types of programme staff will depend on the size of the planned programme and projected

case-loads.

For emergency SFPs, key positions may include;

1. Overall Programme Manager

2. Health workers available to conduct triage and provide medical checks for beneficiaries

3. Supervisor

4. Distribution staff; registrar, measurers, food mixers, health educators and demonstrators, guards

5. Store keeper

6. Outreach workers/community mobilisers for screening, mobilisation and follow-up activities (see

section 3.1)

2.2.2 Supplies, equipment and transport

The size of the area and number of beneficiaries expected for the SFP will determine the amount of

materials, equipment, food and other items that are required.

The minimum supply requirements for an emergency SFP may include:

1. Food commodities; Fortified Blended Food (FBF), oil, sugar and/or other products to treat MAM

(see section 2.3.2.8)

2. Routine and other common drugs and vitamin supplements (see section 2.3.2.6.2)

11

3. Monitoring materials; ration cards, bracelets, referral slips, registration books, reporting formats,

supervision formats (see annex 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7)

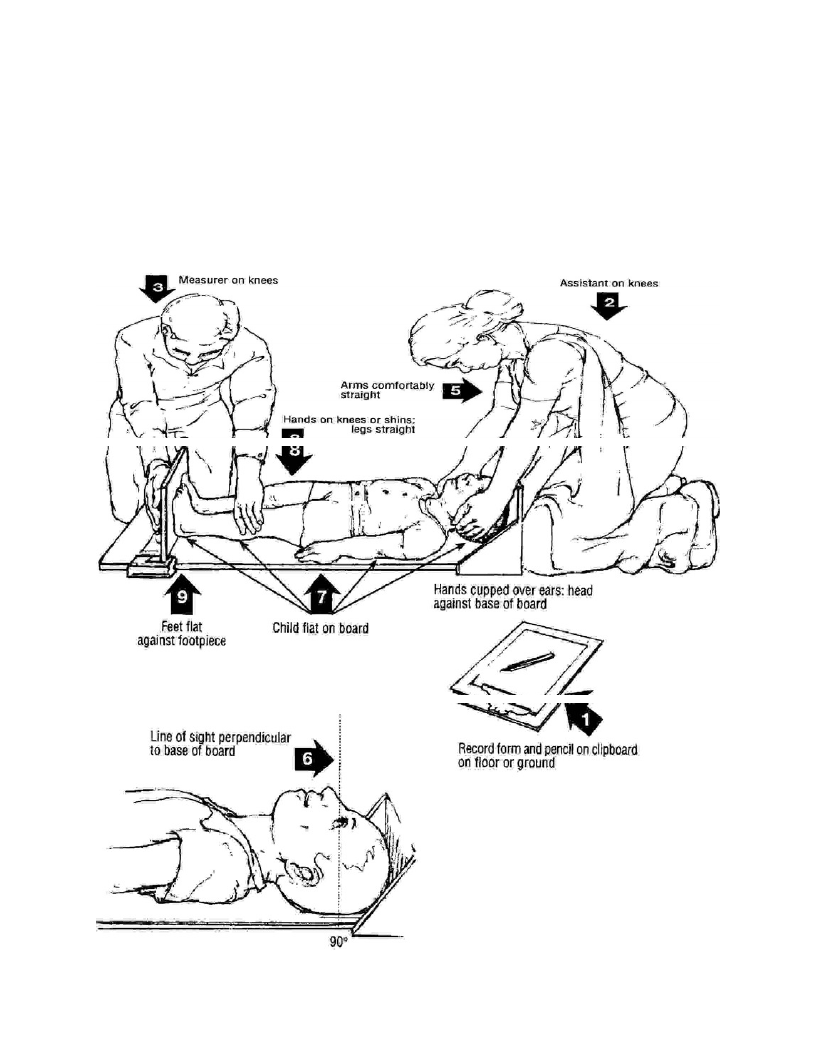

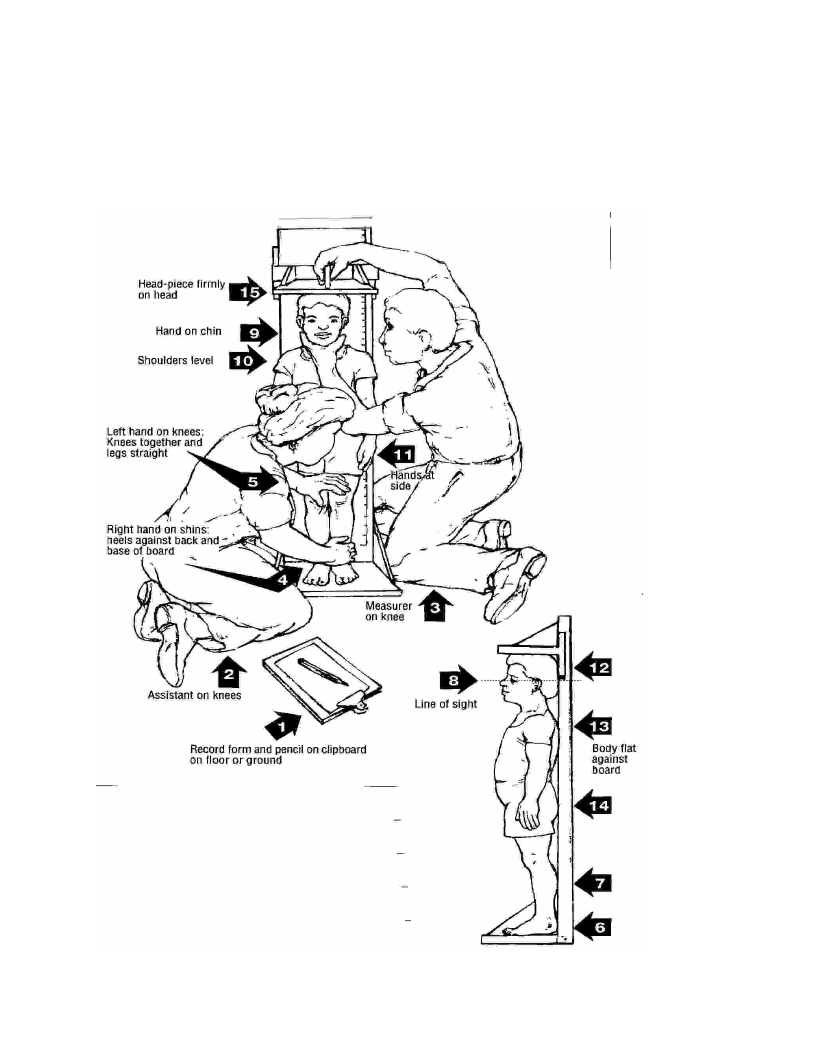

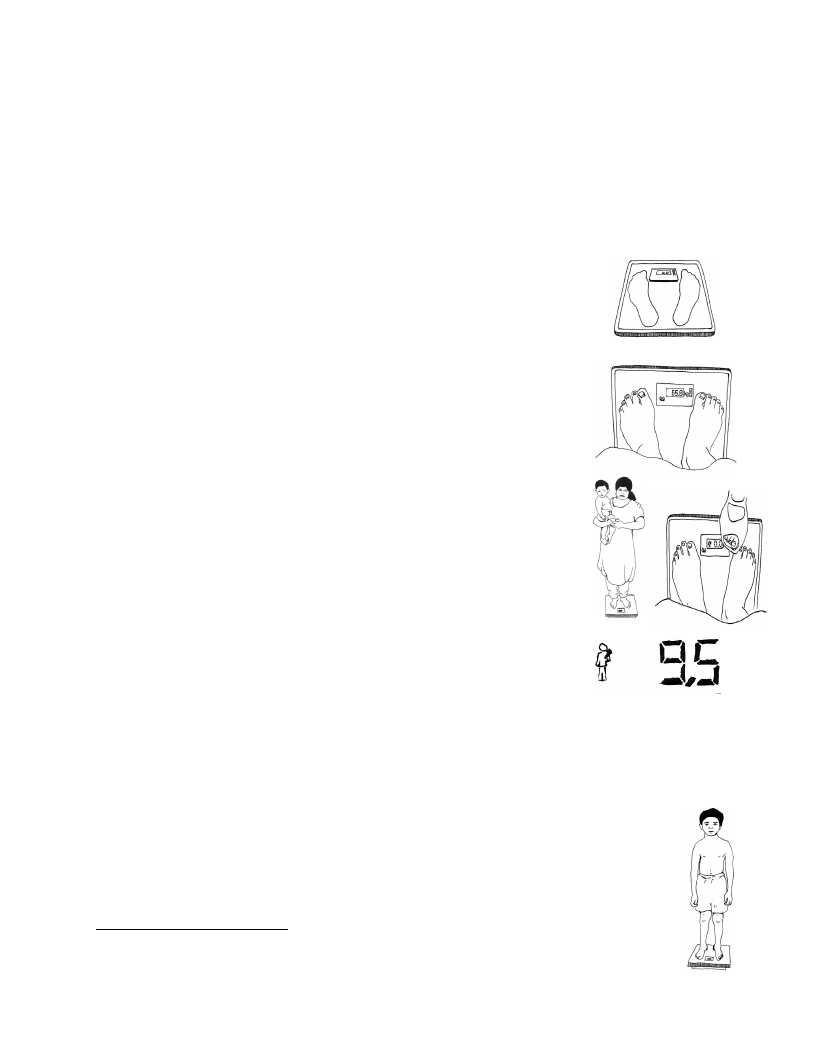

4. Anthropometric equipment; salter scale or electronic scales, height/length boards, MUAC tapes,

WFH reference tables in z-scores (see annex 1, 8)

5. Non-Food Items (NFIs); shelter, soap for washing hands and utensils, clean water, cups, spoons,

cooking demonstration equipment, tables, chairs/benches (see annex 8)

6. Documentation; Information, Education and Communication (IEC) materials, training materials,

National Guidelines, job aids, field guides (e.g. CSB+, RUSF usage), pictorial information for

beneficiaries outlining what they can expect at the site, such as ration entitlements, etc.

7. Sufficient transport must be available to effectively implement the programme; to ensure

uninterrupted product supply chains and to move staff around, as necessary

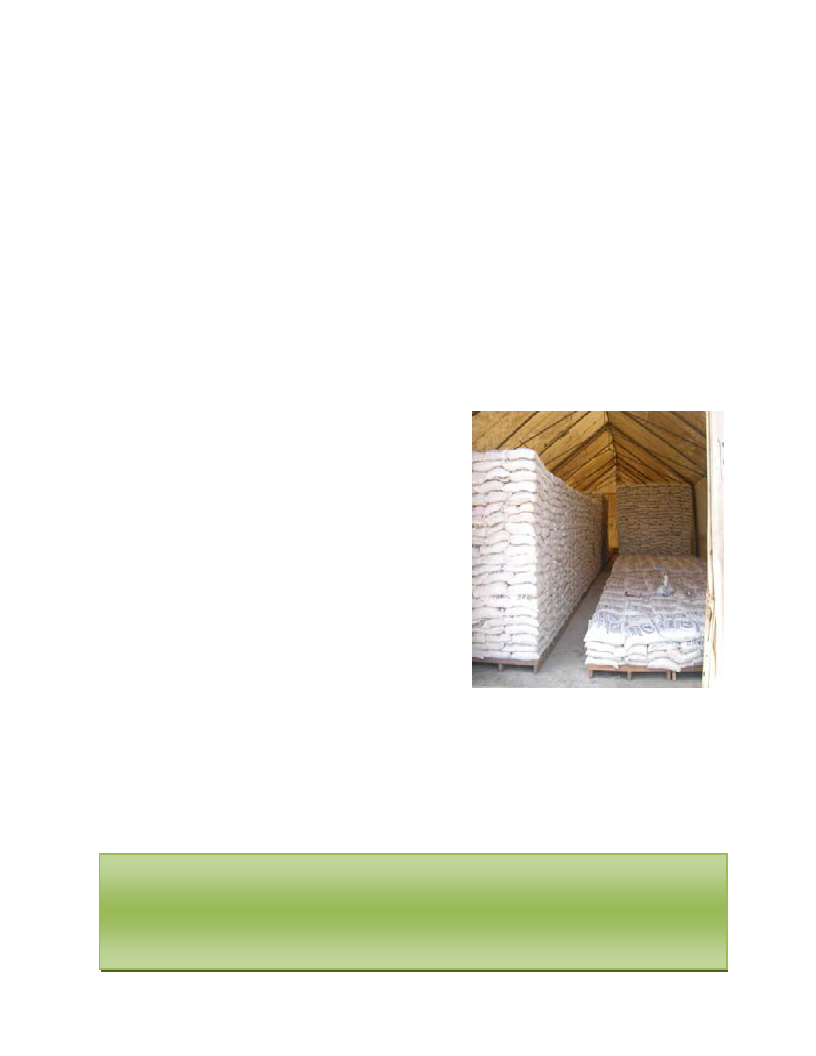

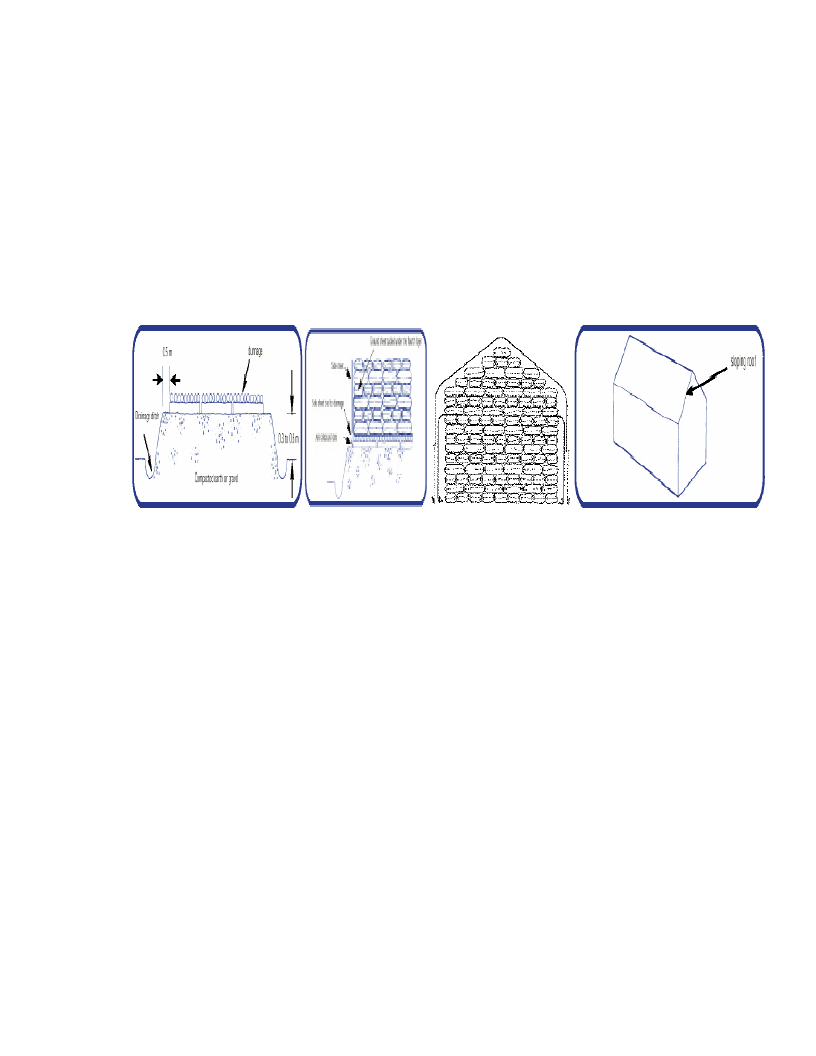

2.2.3 Storage and Warehousing

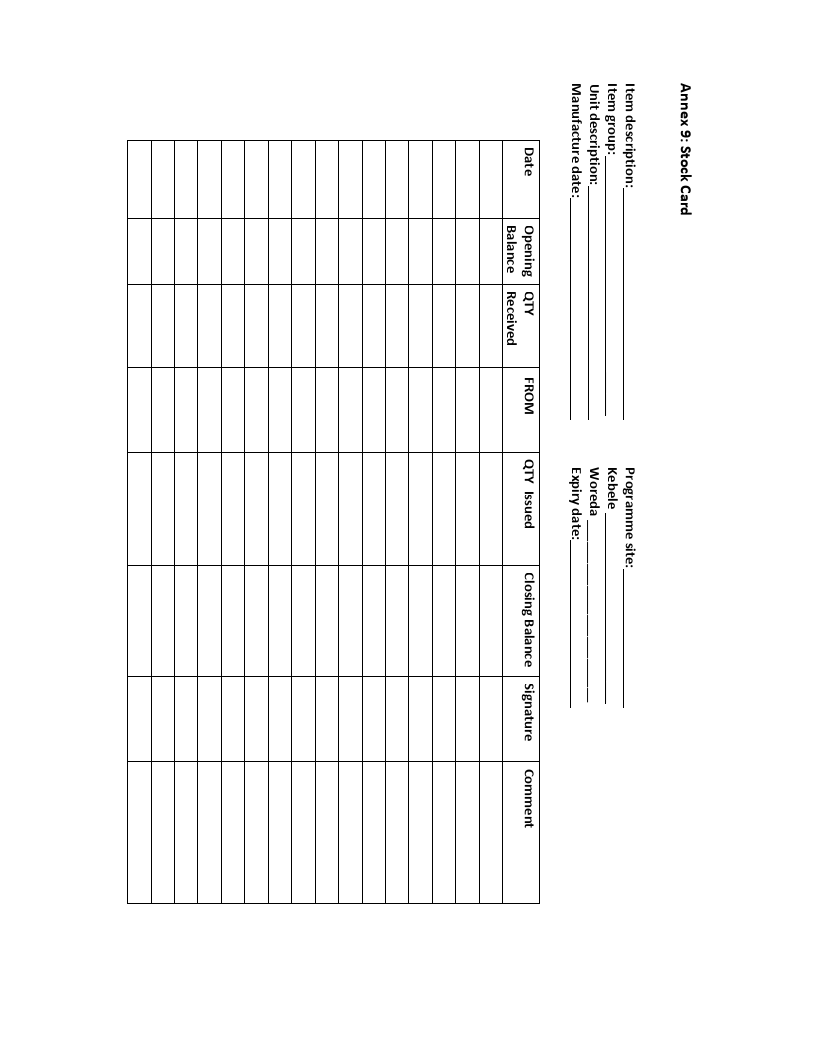

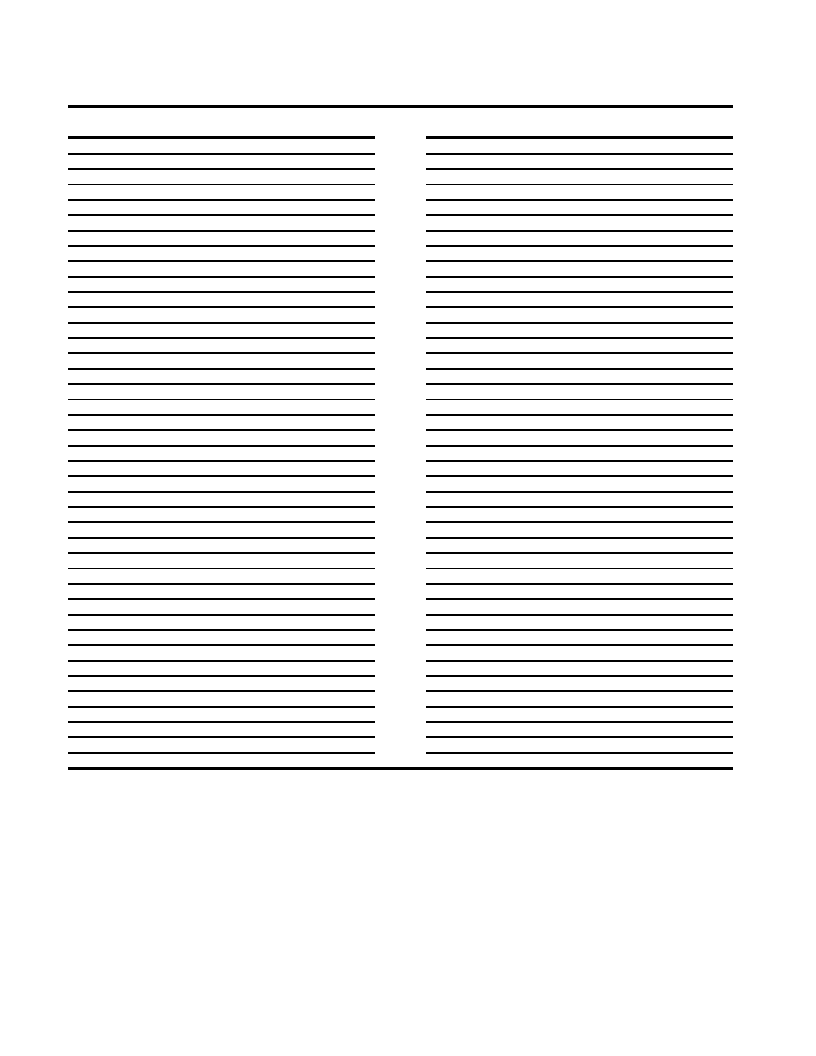

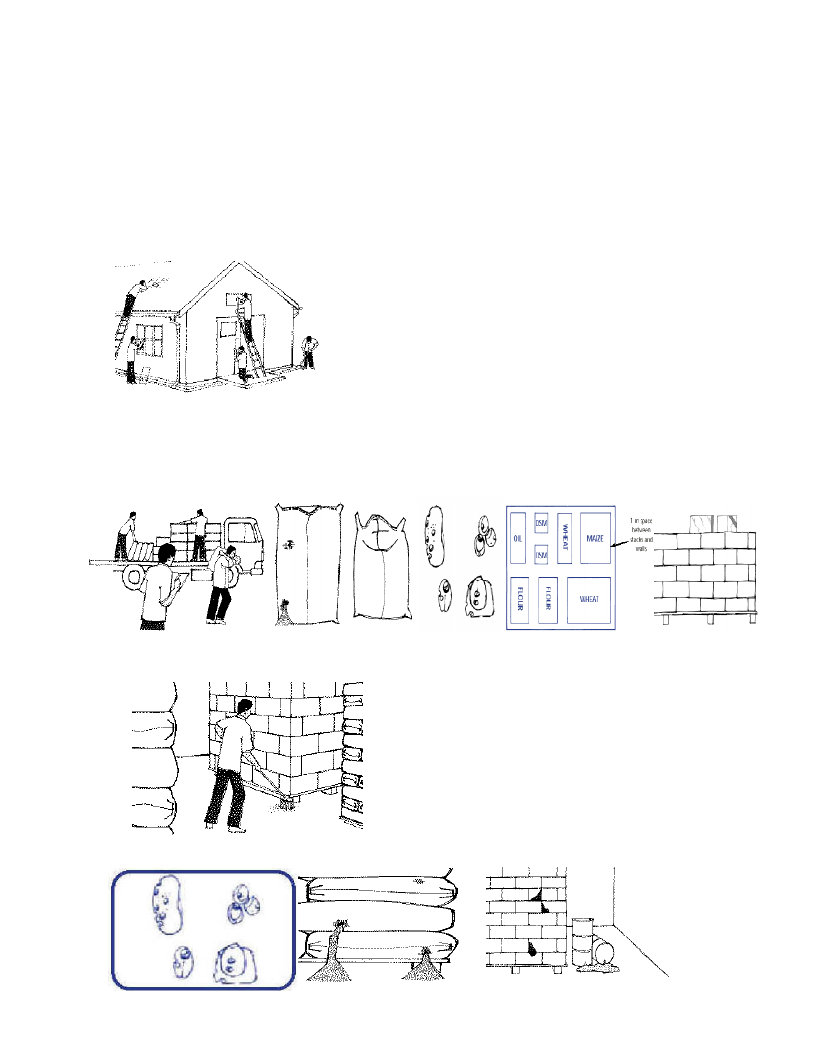

Figure 3: The important features of warehousing and storing food commodities

(Source - adapted from the Somalia MAM guidelines, 2009)

• Products should be stored 40 cm off the wall and 10 cm off

the floor. Food commodities like CSB should be stored on

pallets to prevent weevil infestation/ contamination. Food

commodities should be protected from rodent infestation

• Food products should be stored separately from other

commodities, e.g. medicines or stationary

• Bags must not lie directly on the floor. Stacks of bags should

be no more than 2 m high

• Separate damaged bags/boxes. Record and report any

damage that occurs

• Keep an inventory of all the items in the store; a record list

should indicate name of item, quantity, date received, date

dispatched, from whom, by whom, balance and expiring

dates. It is helpful to have a Stock Control System, using the

‘first in, first out’ storage strategy (but also considering the

expiry date; goods with earlier expiry dates should be used

first). See annex 9 for sample stock card and annex 23 for

tips on good warehouse management (supplied by WFP)

2.3 Types of Supplementary Feeding Programmes (SFPs)

There are two types of SFPs: Blanket or Targeted.

(Source – adapted from UNHCR/WFP Selective Feeding Guidelines, 2009)

The key difference between the two types of SFP is that:

• Targeted SFP target and treat moderately malnourished individuals;

while

• Blanket SFP has a more preventative role, targeting all those in ‘at risk

groups’ irrespective of nutritional status

12

2.3.1 Blanket Supplementary Feeding Programme (BSFP)

A BSFP is a temporary distribution of a supplementary ration to all members of a specified at-risk group

(e.g. all children <5 years, or all PLW, or people with chronic diseases), whether they are suffering from

MAM, or not. BSFPs are generally implemented in a specified geographical area e.g. a camp or woreda.

2.3.1.1 Objectives of the BSFP

BSFPs are implemented at population level, therefore their objectives are primarily preventative. BSFPs aim

to prevent deterioration in the nutritional status of a population, to reduce the potential prevalence of

acute malnutrition and micronutrient deficiency in order to reduce excess morbidity and mortality among

those at-risk, through the provision of a food/micronutrient supplement.

BSFPs can act as a very effective measure to stabilise rapidly deteriorating situations (e.g. very high GAM

levels, during outbreaks or epidemics of infectious diseases, etc.), or they may act as a short term measure

during a seasonal hunger gap. BSFPs are usually implemented alongside a GFD, or can be implemented as a

‘stop-gap’ measure until sufficient GFD can be established.

BSFPs provide a fortified food supplement for all members of the identified vulnerable group. The

availability of resources will dictate the scope of the target group, for example, under-24 months, under-36

months, under-60 months, PLW, etc. Where resources are limited, the priority is usually to ensure full

coverage of children 6-23 months in a defined geographical area.

While anthropometric status is not measured or monitored during BSFPs, staff are encouraged to conduct

anthropometric screening wherever possible, in order to facilitate the correct referrals of persons with

MAM and SAM. As targeted supplementary feeding programmes and BSFPs are not implemented

concurrently, emphasis must be placed on the referral of identified SAM children for further assessments of

complications and appropriate treatment.

All registered beneficiaries receive the same nutritional support over a fixed period of time (e.g. 2 months).

Individual measurements are not usually recorded; therefore it is not possible for BSFPs to quantify

individual outcomes.21

2.3.1.2 General criteria for establishing emergency BSFPs

Refer to the Ethiopia ENI guideline, 2011.

2.3.1.3 Case load estimation and beneficiary identification for BSFPs

Where no definitive population data exists, programme staff should discuss with relevant authorities

(woreda offices, health facilities and local leaders) to establish the population size for the area. Numbers of

potential beneficiaries within the defined groups (e.g. children < 2 years) can then be estimated. Where

population data cannot be obtained from local authorities, other information should be sourced that can

provide the ‘best guess’, for example, use of recent DHS or any other surveys/campaigns conducted in the

area.

21 Harmonised Training Package. Module 12: Management of MAM, technical notes, version 2: 2011.

http://www.ennonline.net/pool/files/ife/management-of-moderate-acute-malnutrition-technical-notes.pdf

13

At community level, beneficiaries that fall within the defined group must then be identified, for example,

children 6 - 23 months or 6 - 59 months (less than 87 cm or 110 cm in height, respectively). This can be

done through the passing of information via local sources, for example, calling the population to come to a

certain area on a certain day to be registered for the programme.

Depending on the seriousness of the situation and in discussion with local and regional authorities, it may

be decided to include other vulnerable groups in a BSFP,22 for example;

All PLW

All adults showing signs of malnutrition

Older persons

Those with a disability

Where possible, effort should be made to provide Vitamin A supplements and deworming tablets during

contact points with the children on distribution days. Where appropriate and resources allow, other

interventions could also complement the BSFP distribution mechanism, such as distribution of Insecticide

Treated Nets (ITNs), water purification tablets, etc. It is important to focus on nutrition, health and hygiene

sensitisation during any contact points with beneficiaries. Appropriate IEC material should be

disseminated/broadcasted.

2.3.1.4 Admission and discharge criteria for BSFP

Admission and discharge criteria for BSFPs do not rely on anthropometric indicators. Once the targeted

groups have been defined, those that meet the criteria are admitted (e.g. children aged 6 - 23 months).

After a specific time period or when the BSFP is closed, they are ‘discharged’.

2.3.1.5 When to Close emergency BSFPs

Refer to the Ethiopia ENI guideline, 2011.

2.3.2 Targeted Supplementary Feeding Programme (TSFP)

2.3.2.1 Objective of the TSFP

The Targeted Supplementary Feeding Programme (TSFP) aims to rehabilitate moderately malnourished

individuals (most commonly children 6 - 59 months and Pregnant and Lactating Women, PLW) through the

provision of nutritional support,

• To prevent deterioration into Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM)

• To reduce the risk of morbidity and mortality associated with MAM

• To provide nutrition/health education and opportunities for counselling

Where required and resources allow, other nutritionally vulnerable groups can also be targeted, e.g.

adolescents, people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) or other chronic disease, older people, etc.

22 Refer also to the 2011 National Guidelines on Targeting Relief Food Assistance. Ministry of Agriculture (Disaster Risk

Management and Food Security Sector), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

14

2.3.2.2 When to establish TSFPs

During times of heightened food insecurity, emergency nutrition interventions such as TSFPs may be

required to complement routine MAM treatment and prevention programmes. For further information

regarding criteria for starting emergency TSFPs, please refer to the Ethiopia ENI guideline, 2011.

2.3.2.3 Determining the case load for a TSFP

For new programmes, the number of beneficiaries can be estimated based on the findings of the most

recent nutritional assessment. Examples are given below for how to calculate the expected case-loads:

Total number of malnourished group =

Total population of vulnerable group X Prevalence rate of Moderate Acute Malnutrition23

For planning purposes, it is common to estimate that between 70-80% coverage of the population will be

reached by the TSFP.

Example 1:

A standard nutrition survey conducted in Borena Zone indicated a GAM level of 14.6% and a SAM of 1.6%.

The estimated total population of the survey area was 50,000. Based on the nutrition survey results, the

estimated number of children to be enrolled in the programme is calculated as follows:

• Total population of the area = 50,000

• Under 5 population (for example, 18% of total population) = 50,000 x 18/100 = 9,000

• Prevalence of MAM = GAM- SAM = MAM level (14.6% - 1.6%)= 13%

• Number of MAM children in the area = 9,000 x 13/100 = 1,170

• 75% of MAM children expected to be reached by TSFP = 1,170 x 75/100 = 878

It can be more difficult to estimate the expected case load of pregnant and lactating women for the TSFP